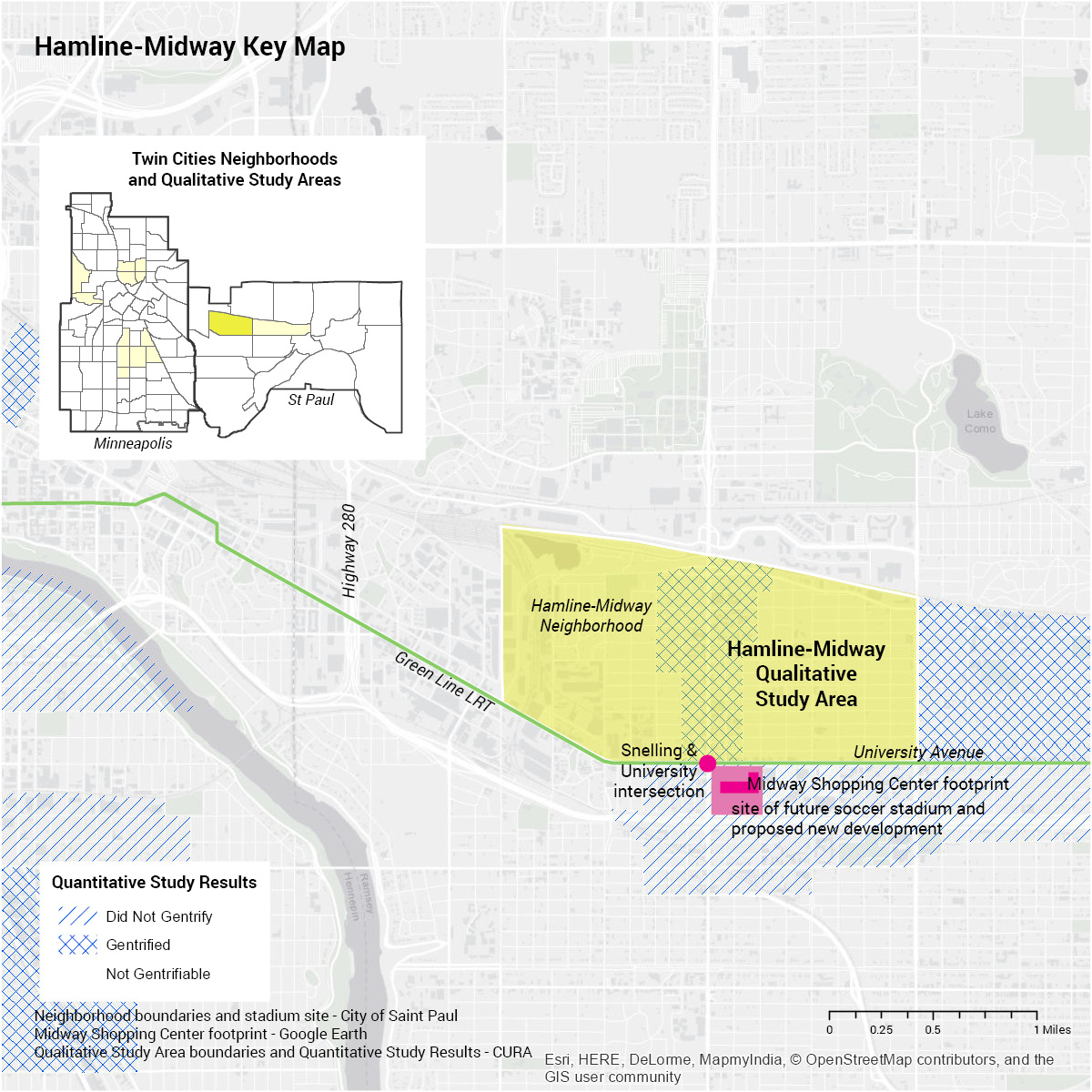

Hamline-Midway, a destination point between Minneapolis and Saint Paul, has historically provided affordability and access to amenities for residents. Yet recently, stakeholders have identified a revived a conversation around an uptick in crime and violence, specifically youth crime. Rising housing costs from west to east, the impact of the construction of the light rail and the new soccer stadium are factors that illustrate impending neighborhood change and the excitement and anxiety that comes with it. These changes have forced residents to look beyond the built environment to the culture of a community and the question of who belongs. The following interview analysis provides a snapshot of the narratives shared by 10 residential and business stakeholders in the Hamline-Midway neighborhood in our study on gentrification.

Visit the Minnesota Compass profile for this area

On the Cusp of Greatness: Hamline-Midway, Crime, and Transformation

“I've heard quite a lot of concerns about the light rail coming in, and what that's doing. How that’s changing the stability of the neighborhood. So, you know, we kind of hear things like, well, there are more rentals now. Yeah, less stability in that way. And then more crime…I think it's just easy to get kind of wrapped up and riled up and feeling things more. I'm not entirely sure it really has increased. But there's definitely a neighborhood sense that it’s increased.”[1]

On May 24, 2017, Ward 4 Council Member Russ Stark hosted a Hamline-Midway Public Safety and Youth Outreach meeting, which included St. Paul Police Department Western District staff and almost 50 local community members.[2] The meeting focused on how last summer went in terms of crimes and disturbances and what improvements could be made for the summer of 2017. In 2016, the Hamline-Midway community definitely experienced increased rates of crime and violence in some areas. For example, between 2015-2016, the community experienced an increase in police calls for service (12%) with additional increases in other areas such as drug calls (15%) and weapon discharge calls (102% increase), whereas the Saint Paul community as a whole experienced decreases in overall calls and drug calls at 2% and 14% respectively and a smaller increase in weapons discharge calls at 27%.[3] The purpose of the May meeting was to involve the community in conversations regarding safety and the importance of creating a safe environment that is welcoming to young people.

Popular wisdom surrounding gentrification often focuses on the results of economic restructuring while neglecting what happens to a low-income neighborhood once they receive an influx of a new affluent class of residents—the social dynamics, even the rules of civility, change. Areas that are going through changes in economics will often draw more police, which create conditions for more surveillance and increased concerns about public safety and public order. Among the community stakeholders that we interviewed there was considerable disagreement between low income renters of color and racially and ethnic minorities in general and a growing population of young educated interviewees, a majority who were white, about the realities of crime and surveillance in the area. Something has changed in the last few years and the question is whether or not it is perception or reality.

Located directly between two major metropolitan centers, the Hamline-Midway neighborhood in St. Paul has historically been a desirable area for those looking for access to affordable housing and low-cost amenities. The western border of the neighborhood houses light industrial warehouses, one of which is now home to Can Can Wonderland, the first arts-based public benefit corporation in Minnesota, whose opening prompted True Stone Coffee Roasters and then the Black Stack Brewing Company to move in next door. Visible shifts in commercial business development have been further supported by the opening of a number of new affordable housing complexes near Highway 280. As you move further east, you will find what many of our community stakeholders argued is one of the busiest intersections in the state, University and Snelling Avenue. North of this busy intersection is Hamline University, which is surrounded by apartment buildings, single-family homes, and those businesses fortunate enough to have survived the light rail construction along University Avenue.

Ten community stakeholders[4] were interviewed in the Hamline-Midway neighborhood. Similar to many residents across the five cluster neighborhoods, Hamline-Midway community stakeholders are noticing a visible change in their neighborhood’s residential demographics, commercial business development as well as increased housing prices that some (not all) fear will displace those families that once sought out the area for its affordability. Unlike, any of our interviews across the five cluster neighborhoods in the Twin Cities, residents in Hamline-Midway have a competing perception of the realities of crime and safety that are making some feel like a part of the problem and others a part of the solution.

This snapshot focuses on the ways that gentrification pressures often exacerbate public safety concerns leaving residents debating amongst themselves about who belongs, and the ways that rising housing costs from west to east, coupled with the new face of local businesses, has come to solidify for some that an impending change is coming but the lasting effects have yet to become realized. Additionally, the development of a new soccer stadium near the former Midway Shopping Center has brought a heightened sense of anxiety as our community stakeholders expressed competing interests in this new project.

The Hamline-Midway Public Safety and Youth Outreach meeting opened with a report from the Saint Paul Police Western District members. Senior Commander Steve Anderson reported that although some crimes were up - theft (5%), vandalism (1%) and weapons discharge (26%)- overall all crimes reported in Ward 4 were down from the previous year. Yet community residents reported two main concerns from the meeting. First, some neighbors were hesitant to report crimes or suspicious activity to the police, because they were worried about hostile interactions between the police and young people. Secondly, neighbors and business owners cited some of the challenges that they had experienced along the Snelling Corridor between Minnehaha and University Avenues and in the Hamline Park area much associated with public nuisances.

The data shows an increase in criminal activity in certain areas in Hamline-Midway, while overall, all crimes in Ward 4 were actually down. In fact, the increased level of criminal activity lies within the gentrified zone that the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) quantitative maps highlight distinctly. “The theory goes that as demographics shift, activity that was previously considered normal becomes suspicious, and newcomers—many of whom are white—are more inclined to get law enforcement involved. Loitering, people hanging out in the street, and noise violations often get reported, especially in racially diverse neighborhoods.”[5] This heightened level of awareness often coincides with a larger number of 311 and 911 calls focused on “quality of life” crimes increasing the presence of police officers on the streets.

Is It Perception or Reality? Crime in Hamline-Midway

Perception is everything. As Hamline-Midway begins to see once vacant commercial buildings no longer vacant, higher home values, increased rents, the rise of arts-based nonprofits, breweries, vape shops, and historic mom and pops disappearing, everyone is developing their own understandings of how these changes will affect their immediate and long-term experiences in the neighborhood. However, the uptick in the conversation surrounding youth crime in the neighborhood during the rise of these major public and private economic investments presents some competing viewpoints.

“Yeah, there's going to be more attention to those crimes and more people gathering because they're seeing all the good going on and they're like, ‘We want to continue to keep cleaning this up and-- let's start calling the police more. Let's get rid of this group of kids,’ rather than raise them and try to get them to doing something positive. ‘Let's try to continue to push them out or push them away,’ because I'll say it again, this new stadium's coming in. There's new stores over here. The demographic of people that were already here that have been doing the same thing are now being pushed to certain specific areas that limit them, you know?”[6]

Our community stakeholders are engaged in a fairly heated debate about the public perception and realities of youth crime in the neighborhood, especially as many acknowledge that with increased economic investment has come a heightened need for order and policing from other stakeholders. A long-term renter of color expresses a bit of irony as she argued that crime has always been an issue in the area, which all families, irrespective of race or class, have expressed concern about over the years. However, this community stakeholder argued that a new level of attention has been given to the conversation in the last few years, signifying that a new residential demographic has arrived and are using their power to influence the direction of the neighborhood’s resources.

“This is kind of cyclical in our neighborhood, but there always seems to be this uptick in concern around crime that happens in the conversations. And that has happened in the recent couple of years. There's been a lot of concern about youth congregating in our neighborhood or quality of life issues along University Avenue. And I feel like it kind of-- as the neighborhood becomes more attractive to certain people that conversation has started.”[7]

Gentrification’s impact goes far beyond the physical built environment and rising costs, but also the creation of a new cultural way of being and living that is often hostile to any markers of urban deviancy that so many fled from during the era of white flight. As younger white families and professionals return to the central city in search of an urban living experience, many are bringing with them a set of values and frames about urban living that certainly influences how they understand what community actually looks and feels like.

“There has clearly, in like a very small space, been an up-tick in open drug dealing, some, a few violent incidents. I mean, so like we've heard gunshots or had gunshots within a few blocks of our house probably four times over the last year, year and a half. So that's real, right, like when bullets are flying, that's real. And that changes even the most kind, progressive-minded person who like very much cares. At least they say they care about things like racial equity and whatever they think that means. They care about those things, but the second, what I've heard from at least a couple people that I know well, young white women with small kids, is the second you start to feel like your kids are(?) being traumatized by it, and they're seeing it and they're witnessing it, and they're fearful of black men walking down the street, things like that, that changes. Like all of a sudden, you can care about trying to push to have, to dealing with these things in a positive way, but you want that shit gone, right. Like no matter what, you want that shit gone.”[8]

In the aforementioned quote, a newer white homeowner discusses a number of violent occurrences that took place along Snelling Avenue near Hamline Park, all of which are legitimate concerns for any community. However, the assumptions made within this stakeholder’s analysis provides a sense of how values shape how we are experiencing any given traumatic occurrence in our lives, especially considering that this stakeholder stated earlier that he bought a home in the area because he was sure it was going to “pop.”

This racialized juxtaposition of the young, white mothers who are fiercely protecting their children from the trauma of witnessing violence that is then associated with young black men walking down the street, places men of color in an unproven, unwarranted and precarious place and makes them the target for removal or the body to be feared. What is important about this discussion is not just that it is happening, but rather how it is happening. As demographics begin to shift in the neighborhood and younger, white families move into the neighborhood and become more visible, so does the identity of those who get to control the narrative surrounding youth crime.

“For whatever reason this summer, particularly this summer, there was just this swell of concern, particularly around youth and them being together, congregating together. And folks were saying they were intimidated, that they felt unsafe because of the congregation. And when the question was asked - and I've been in a couple of community meetings - like, ‘Well, what are they doing?’ There would be things like, ‘Well, they're being loud, and they're fighting, and they're whatever.’ I guess, to me, those are not new things…It's not like the behavior has significantly changed [since she was a kid] either. So I guess I'm kind of confused. Why is there this newfound fear of these kids that I don't necessarily see anything significantly different about the behavior that they're showing?”[9]

...

“I've been part of some of these police meetings because I feel like you have to be at the table, right, and a lot of the young people that were involved in crime or drugs don't live here. So in the last year or two they were seeing when there would be fights and there would be like 50 people, the stuff that ends up on the internet, that they were finding, and I think it is probably mostly true because we saw lots of people we just didn't recognize, were people that weren't from the neighborhood. I don't know if they were necessarily from Minneapolis or different parts of Saint Paul, but they weren't, they didn't appear to be people living in Hamline-Midway. So that changed the discussions too. It's like it's one thing if it's our kids and we can try to focus on them and their families and creating a more welcoming environment. It's another thing if you're coming into our neighborhood and it feels like we can't stop them.”[10]

The new white homeowner, who moved to the neighborhood about seven years ago, stated that those youth engaging in violent activities were not “our kids.” He makes a point to note that if they were, they and their families would be welcome within the neighborhood. But what gives this stakeholder the right to politely, yet firmly identify who belongs and who does not? Who has the right to claim ownership over community?

An ownership society presumes that through owning one’s own home or other capital investments in one's own community, you will be more invested in the future growth and development of that space. For non-owners, they presumably lack the “will or desire” to own and are thus not as deeply invested as those with economic buying power, which is a narrative that can make non-owners feel a lack of belonging to their neighborhood and a fear that their lives are being shaped by outside interests rather than their own. Often what is stated in rather veiled language presumes that certain residents do not belong or do not fit normative standards of civility that newer residents believe is viable. The introduction of the light rail to this community has helped to bolster the perception of an increase of people, who may or may not belong, coming into the neighborhood.

Transit Oriented Development, Housing, and Gentrification

“I didn't know much about either of the Twin Cities, but I felt comfortable taking a chance either way, that there was enough good things going on, enough good people. And then wanting to be in the heart of everything, so Hamline-Midway-- it's called the Midway for a reason between the downtowns in Saint Paul and Minneapolis. So I still go to Minneapolis all the time, so it felt like a good place. We knew the light rail was coming, so that certainly played a role. The ability to get back and forth pretty easily to the two cities downtown. Snelling -University is, as you know I'm sure, pretty much the busiest intersection in the state. So it seemed like there's something there. We didn't know exactly what, but it seemed like if you want to be in the center of the action, it's not downtown Saint Paul.”[11]

…

“A lot of commercial businesses don't have a huge for-sale sign on them. And it seems to me that the goal is just like, ‘Hey if someone wants to pay us 3 or 400,000 dollars more than we paid for it five or ten years ago, we're going to take that. It's very clear that there's a sense that this neighborhood's going to pop in certain ways. And so we can get developers to overpay for these. And that's been very upsetting to me.”[12]

Areas adjacent to transit stops typically experience thriving commercial activity as new shops, restaurants, and businesses attract and make accessible once neglected urban corridors to commuters and non-commuters alike. The Hamline-Midway neighborhood is at the heart of the Green Line light rail, which was a project that aimed to spur economic growth and access stimulated by increased public and private investments. Improving access through transportation increases the desirability of a neighborhood, which has been shown to increase residential property values/taxes and subsequently increase commercial property land values. Local community stakeholders are not only seeing these trends, but are finding that their ability to maintain residency, build community, and see a future in this neighborhood is often placed into question because of these targeted urban redevelopment approaches. Community stakeholders are actively seeking out “up and coming” urban corridors like Hamline-Midway, because they are certain that the neighborhood will pop and they want to directly benefit.

“Well, what I notice is the improved housing. And I think I've noticed more, I don't know, maybe a little less international, a little more hipster.”[13]

…

“And this neighborhood has turned very crunchy because of it [New incoming urban professionals or artists]. Oh, my goodness. We have huge bicycle advocates in this neighborhood. We have huge environmental advocates in this neighborhood. We have lots of people who keep chickens in this neighborhood. Yeah, so that is…I think, would have been unheard of, when we bought our house in '92 because it was, like I said, very solidly working-class then. Much more so than it is now.”[14]

…

“But then anytime I move beyond that [near the Northwest corner of University & Snelling] or into the neighborhood it gets more expensive. And those apartments, I mean, those used to be all kind of the same. And then anything kind of in this area, near Fairview, there used to be a lot of affordability. And I don't see those apartments-- I was looking at one listing that said the apartment was like $1,100 and I was like, "What [laughter]? Where did that come from?" And what I'm seeing is, some of the apartments they're doing some significant renovation, but even with that, to jump from where certain apartments used to be, like I said, in the 600s to 700s, now you're talking about 800, 900, 1,100, that's significant, so.”[15]

…

“I do own a house now and I am shocked at how expensive housing is right now. I recently tried to help friend get out of a situation and it was kind of a financial barrier. All of the apartments are way more than my mortgage. I have no idea how anyone does it. It is something that we think about…we, I would say about 2/3 of our staff right now make a living wage, and we have a goal for everybody to get to a living wage of 15 dollars an hour by the end of the year. Even with that, I mean how do you? You have to live with people, to be able to afford a place to live. That's insane.”[16]

…

“Well personally, I have a new landlord. The first thing that the new landlord did was raise my rent $75 a month, and just incidentally upped the coin-operated washer and dryer by double, so it's now $2 instead of $1. That may seem a little bit petty, but I think it all plays in.”[17]

From descriptions of a visibly younger, whiter, hipster, crunchy crowd that is more environmentally friendly and desires alternative food choices to a housing market that has become so unaffordable that many (mostly renters) are being forced to move further east away from Highway 280, our community stakeholders make note of some alarming trends that are leaving many to question who will benefit from these changes undoubtedly spurred by transit-oriented development.

“So Midway Shopping Center has kind of always been a part of a conversation of like, Can we improve that space? Can we make it a better space? And can we put more quality shops in that space? Or quality things, family friendly things? And listening to it, I think there are people who come to that space. That's their only place that they shop for food. That's the only place that they shop for things. I mean, Walgreen's, the Rainbow, the places that are there are available to them in a place where they can walk to or they can transit to easily. If you take those things away, suddenly where do they go when you have different things available? So that's where I feel like there's a-- like these things aren't good enough. We want better things, but then the people who have kind of been shopping in that space who have been utilizing the space, who have been going to the bars that exist along that space. Where do those people go then? And are the improvements that are being made for the folks that have been existing in the space?”[18]

As community stakeholders come together and talk about the impending changes coming to the University and Snelling Avenue corridors, many are questioning whether or not those residents that originally sought the area for its housing affordability and the low-cost amenities that were easily accessible at the former Midway Shopping Center, will be tomorrow’s desired customer after it is redeveloped. Or will they be deemed a part of the problem and weeded out?

“I feel like people who have been utilizing that area [former Midway Shopping Center], who have been shopping in that area, who have been going to the businesses in that area, are now seen in some ways as undesirable to be in the neighborhood even though they've been the ones to predominantly be the ones to work, kind of economically driving the neighborhood. So that's some of the things that I'm seeing now.”[19]

…

“I think that's what it will attract-- hopefully, that’s what the soccer stadium will attract. The kind of restaurants, bars, retail that brings in people that haven't been used to coming to Midway. Like other areas of Saint Paul don't offer them… Probably it won't benefit the people that currently shop here. I think it will attract other people.”[20]

The realities of a gentrified neighborhood tell us that with new tastes comes new businesses and new customers that will push out the existing residents and perhaps simply eliminate those spaces and places that made former residents feel a sense of community. Hamline-Midway is transforming and the decisions that were made to ignite these changes have produced a series of reactions and subsequent investments that are shifting the culture and accessibility of the neighborhood. Many of our community stakeholders see a neighborhood that was once riddled with vacant commercial properties, which are now up for sale or have sold as a visible sign of a neighborhood that has become more economically attractive. But a neighborhood like Hamline-Midway loses something in the shuffle of becoming more economically viable that some community stakeholders mourn, others resist, and those in more economically powerful positions praise. The community stakeholders we interviewed vividly described the ways that transit oriented investment has ushered in both a demographic change and rising housing costs producing lasting effects they have yet to fully comprehend and immediate hardships for others.

Concentrated Economic Development and the Fear (or Joy?) of Stadiums

For Hamline-Midway stakeholders, the light rail construction was just the beginning of major development for the area. Just adjacent to the neighborhood cluster, on the southeast corner of University Avenue and Snelling Avenue sits the remnants of the former Midway Shopping Center followed by an expansive dirt-filled lot that has become home to bulldozers and cranes – the signs of new construction. The former Midway Shopping Center used to house businesses such as Rainbow Foods, Big Top Wine & Spirits and a Chinese buffet – all of which are slated to be demolished for the construction of the new stadium.

“And so they'll have to tear down pretty much everything from Snelling to Pascal, kind of, yeah, south of McDonald's and an area to build it. So that's something too they're [residents] talking about, the jobs of displacing the workers because Rainbow would have to be torn down, Walgreens, the bowling alley, Big Top Liquor, and all those different things.”[21]

…

“I've heard people negative about soccer because there's no parking. In their minds, there's going to be no parking. The neighborhoods will be-- Well, they say run over on game day.”[22]

The soccer stadium has reignited anxiety over a potential impact similar to that when the light rail was under construction. As of June 2014, 121 businesses had closed or moved away from the Green Line corridor during construction.[23]

“There was a Korean Heritage Center that was pushed out because the owners wanted more money so they would have been doing-- and the woman who runs that was forced to move to a smaller space which is really unfortunate because it-- it was unfortunate to begin with, even more unfortunate that it was taken over by a e-cigarette, a vape shop.”[24]

Yet, the increased anxiety is not only based on the viability of small businesses’ ability to thrive when impacted by major construction, but the displacement of amenities for residents who not only depend on the services, but have historically been the main patrons of the area.

“Mai Village[25] there down in Little Mekong, but that's a sad-- the owner is so nice. And he owned Mai Village for 11 years and then they closed down and did this huge renovation. They did this huge renovation and opened this gorgeous restaurant and it was like 7 million dollars and he had it paid down to 1 million and light rail construction came through and just crushed them. It was like, wow, like why can't… like that is heartbreaking. And so that is definitely one of the worst gentrification…”[26]

Although historic residents of color and small business owners are bracing for the impact of the new the soccer stadium development, big business owners can embrace the investment opportunities that come with community redevelopment. Since the opening of the light rail in 2014, $4.2 billon dollars has been invested along the Green Line[27] and major financial investment is predicted in the development of the new soccer stadium as well. The site surrounding the new $200 million dollar soccer stadium is expected to receive over $18 million in infrastructure investment to just begin to make the stadium project possible.[28] Big businesses, with significant capital, are poised to benefit from these investment opportunities as well as the increased emphasis on creating a more “vibrant” community, oriented to a higher end clientele.

“I think vibrancy would just bring a lot more excitement and interest. And I'm seeing more international and more of a mix of people. I think upgraded retail. Upgraded both retail, restaurants, entertainment… you know, they’re talking movie theaters. So I think it will be much more of a destination. I mean that's our hope.”[29]

One community stakeholder that works in the former Midway Shopping Center stated that he also desires more vibrancy, but with a much needed change in demographics, specifically the overpopulation of homeless patrons in the area. He reported that many customers have expressed feeling uncomfortable because of the presence of the homeless.

“And just the bums who come in and would see you two ladies walk in and ask you for a couple of extra bucks. And if you're with kids-- you're scared at first, if you're not used to it. And you're not coming here anymore. You might pay a little extra to go shop at a different store where there isn't anyone bothering you... So, somehow the city has to take care of that problem.”[30]

Although the completion of the Green Line light rail project and the impending soccer stadium and surrounding redevelopment aim to continue to help spur economic investment and growth in the area, many community stakeholders have acknowledged that these investments are not only being used as a vehicle to revive the area economically, but have forced a neighborhood in transition to come face to face with the challenges that increased accessibility presents. For some increased accessibility has brought new individuals, specifically young black youth, into a neighborhood in which they do not “belong.” Most of our community stakeholders in Hamline-Midway have reported an increase in incidents and conversations surrounding youth crime and violence, which many connect directly to the accessibility that the Green Line light rail has provided. Some feel Hamline-Midway is on the cusp of greatness, while others watch with hesitancy and concern over the precariousness of the neighborhood’s future.

[1] HM#4: White, female, renter

[2] https://www.stpaul.gov/departments/city-council/ward-4-council-president-stark/hamline-midway-youth-engagement-public

[4]Of the 10 residents and business stakeholders, 7 identified as White and 3 as Black; 4 males and 6 females; 2 homeowners, 3 renters, 1 long-term resident (10+ years) and 4 business owners.

[5] https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/12/the-criminalization-of-gentrifying-neighborhoods/548837/

[6] HM#2: Black, male, business owner

[7] HM#5: Black, female, renter

[8] HM#6: White, male, homeowner

[9] HM#5: Black, female, renter

[10] HM#6: White, male, homeowner

[11] HM#6: White, male, homeowner

[12] HM#6: White, male, homeowner

[13] HM#7: White, female, business owner

[14] HM#10: White, female, long-term resident (10+ years)

[15] HM#5: Black, female, renter

[16] HM#9: White, female, business owner

[17] HM#1: White, female, renter

[18] HM#5: Black, female, renter

[19] HM#5: Black, female, renter

[20] HM#7: White, female, business owner

[21] HM#3: Black, male, homeowner

[22] HM#8: White, male, business owner

[23] https://www.funderscollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/BRC_0315-1_Final_Report_10.pdf; There has been a net gain of 13 businesses since the construction of the light rail with 134 new businesses joining the community.

[24] HM#6: White, male, homeowner

[25] Mai Village was located in Frogtown, but was a University Avenue staple that Hamline-Midway stakeholders remembered fondly

[26] HM#9: White, female, business owner

[27] https://metrocouncil.org/News-Events/Transportation/News-Articles/Development-along-Green-Line-soars-to-more-than-$4.aspx

[28] http://www.twincities.com/2017/08/18/minnesota-united-owner-buys-last-building-near-st-paul-soccer-stadium-site/

[29] HM#7: White, female, business owner

[30] HM#8: White, male, business owner