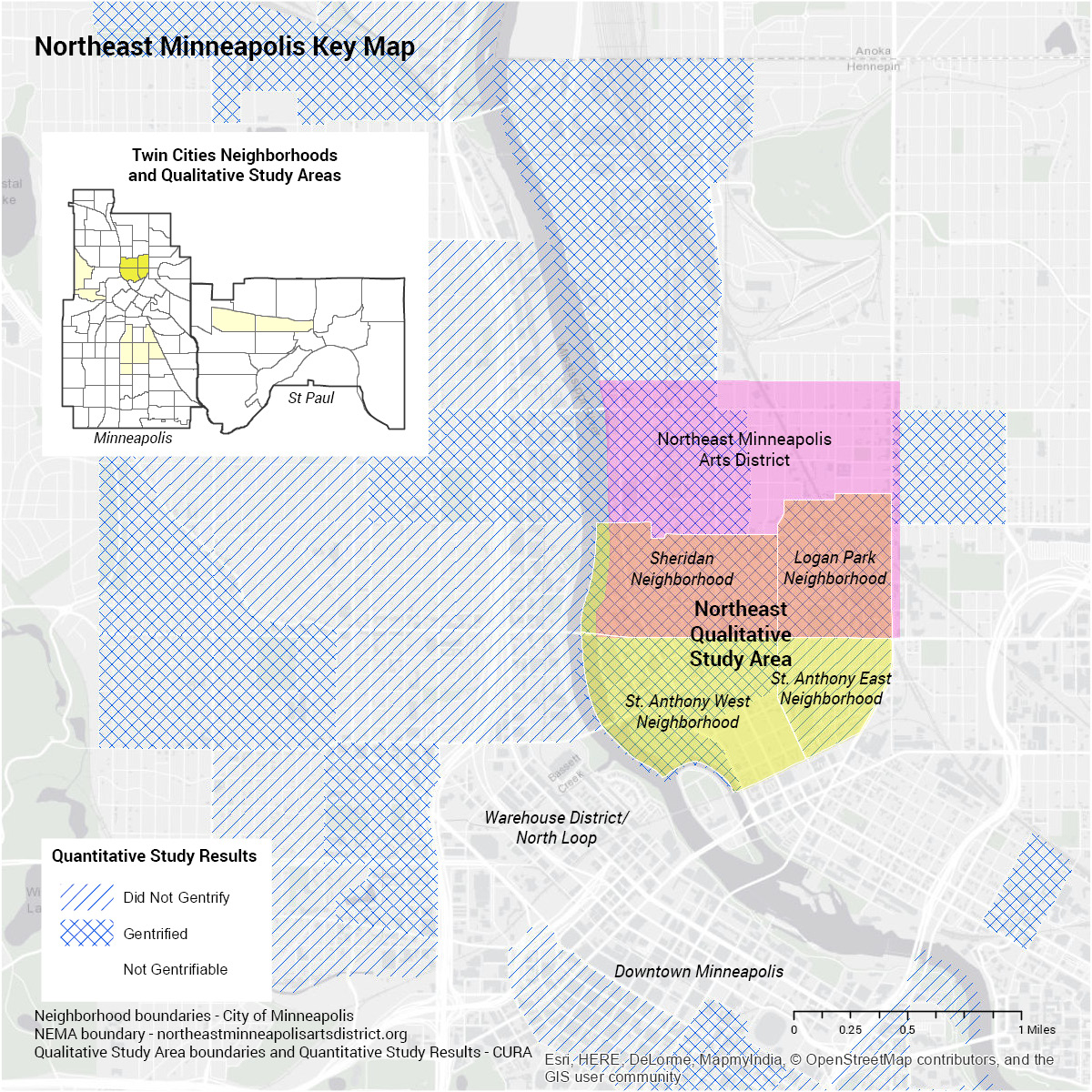

Northeast Minneapolis has become one of the most sought-after destinations in the Twin Cities with a thriving artist culture, the highest concentration of breweries in the city, an abundance of new trendy restaurants, and other creative industries. Historically, Northeast was a working-class, Eastern European immigrant community that was transformed when major industries left the neighborhood providing an opportunity for artists seeking the freedom of large, abandoned, warehouse spaces to create community. After these artists established themselves in the neighborhood and began to host events to introduce their art to a handful of local buyers through what is now known as Art-a-Whirl, an artist culture of “makers” began to thrive. Key stakeholders have identified the economic boom in Northeast Minneapolis as a result of the commodification of a rich artist culture. In turn, Art-a-Whirl has become less about the art and more about the music, beer, and the bands. This rapid economic growth has caused historic residents and artists alike to report steep increases in rents, housing values and property taxes, leaving residents to question whether or not Northeast will continue to be an affordable place to call home. The following interview analysis provides a snapshot of the narratives shared by 13 residential and business stakeholders in the Logan Park, Sheridan, St. Anthony East and St. Anthony West neighborhoods in our study on gentrification.

Visit the Minnesota Compass profile for this area

The Arts and Gentrification: Northeast as a Destination Center

Historically, Northeast Minneapolis (known locally as Nordeast) was an industrial hub that attracted immigrant labor from Eastern Europe. In the 1980s, the area now known as the North Loop was a place that provided unregulated live/work space accommodations in mostly underutilized or vacant industrial buildings. Former, working class artists utilized these large unregulated spaces until razing took place and new developments came with stricter city regulations. Many artists flocked from the North Loop area to a fairly deserted Northeast industrial community, because their work often did not yield immediate fiscal gains and in order to support their work and family they needed large cheap spaces that could serve dual live/work functions, which their former dwellings provided.

“The first time I came to Northeast, it's Polish immigrants who've been there for generations in the quiet, domestic, industrial America. And then a lot of the big warehouses have served in the milling industry, manufacturing, and they're going into an abandoned thing because everybody's building their new factories out in Eagan … So industry is leaving the central city…Then the arts population being forced out of downtown and up-- the population of, what, 300 people at that time, with families, so they come in …Then they can use NRP money to buy homes, so all of sudden, particular individual homes are getting rebuilt. And really, fine work because these are artisans, so they know how to cut wood…Then, all of sudden, storefronts that were abandoned and empty, they also become occupied spaces by creators.”[1]

…

“I think really when I came here, this community was desperate to figure out what was going to happen to it. I mean, all these large-- Grainbelt had left, Northrup King had left, these were like core-- this is kind of where people worked and lived and all those kinds of things, and all of that industry was leaving. And they didn't know their next step. They didn't know what would happen with it. Would these buildings just sit and rot? They didn't know. So slowly the arts started building up.”[2]

When artists arrived in Northeast they encountered a neighborhood rich in social capital. More than half of our community stakeholders described the community as a place filled with blue-collar workers that had a set of shared values, which enabled neighbors to trust each other and work together. Many stakeholders talked about a community full of churchgoers with a strong work ethic that went to work, went to church, and went to the bar. However, that working-class history of “knowing thy neighbor,” according to these community stakeholders, shifted drastically in the last decade, because long-term residents and artists are being priced out while witnessing a shift in residential demographics and a boom in the rise of commercial businesses. As the economic incentives for investment in Northeast became realized, all of our community stakeholders identified changes in housing and commercial leasing costs, residential demographics, and the commodification of the annual Art-A-Whirl event as the moment at which they realized Northeast had gentrified.

Through our interview with 13 residential stakeholders[3] we found that the consequences of creative placemaking in Northeast Minneapolis has produced a context where the market has chosen who the winners and losers will be based on their profitmaking models. The prices have gone up and if you cannot compete you are on the proverbial chopping block. In short, the act of creative placemaking has driven Northeast Minneapolis’ unique form of gentrification in the Twin Cities.

“I also work at the bookstore on the corner...And the bookstore's only been there for three years, a used bookstore is a great thing on the corner. And the landlords are making a profit off of the rent they’re paying. But, the building sold, and the new landlords realized that they can get $1,500 more a month than what my boss is paying for rent right now. So, we're getting kicked out because he wants to put a hip restaurant in that space, and now the bookstore has to move, you know? And he's making a profit on the rent that he's charging the bookstore right now. It’s doing fine, but it’s because they can.”[4]

…

“I used to say it's the beginning of the end because I saw architects move in. Architects and designers are like the canary in the coal mine. When they take over a storefront or something, I go ‘whoa. Okay, we’ve got to start looking for the next place.’”[5]

Art-A-Whirl

Our interviewees in Northeast Minneapolis cited the commercial commodification of the annual Art-A-Whirl event as the sure sign that Northeast has gentrified. Art-A-Whirl is an open studio artist tour, which began with just 12 artists in 1996 with limited spectators and has now grown to more than 600 artists with 30,000 spectators from across the state and country attending for not only the artists, but also for the beer and the bands.

“Art-A-Whirl starts with a group of 12 of us sitting in a studio going, ‘Hey, man. Let's open our places and invite each other's clients up and see if we don't pick up new business or new friends.’ So that's kind of how it starts, and it's all visual arts, strictly what we call the plastic arts, painting and sculpture and drawing and print-making and that's it. Then it starts to develop, and it's a big hit. And then NEMMA gets involved. NEMAA is the Northeast Minneapolis Arts Association. And it's a formal bureaucracy.”[6]

...

“I think Art-A-Whirl is probably the primary reason that Northeast has changed and, well the artist community, moving here. Art-A-Whirl is an outgrowth of that. The artists moving here is why Northeast is gentrifying. And Art-A-Whirl came out of the artists. If Art-A-Whirl wouldn't have happened Northeast would still be gentrifying... It might have not happened as fast.”[7]

…

“When I lived in Northeast, one of the funniest things that we would do is go to is go to Art-A-Whirl and this is 15 years ago...And then you would read in the art newspapers, "Come to Art-A-Whirl, 175 artists." And then the next year, "Come to Art-A-Whirl. There's 225 artists." "Come to Art-A-Whirl. There's 275 artists now." And every year, you could just see that it just kept on growing and growing.[8]

…

“Now it's more like Mardi Gras than any kind of real fine arts event.”[9]

The commercial commodification of Art-A-Whirl took an event that was organized to help a small group of artists showcase their art to high-end buyers in hopes of selling one or two pieces that would sustain them and their families economically for a few more months and turned it into the country’s largest open-studio tour, a combination art/music/drinking event where hundreds of artists are on display to thousands of attendees.

“We [the artists that fuel the creative economy] are larger than sports. We are larger than almost all other industries and our impact is in the billions of dollars because the breweries are selling the beer because the artists are there. So, what happens, as gentrification comes in and changes the fabric of a neighborhood, it also starts to drive up an economic powerhouse that services that changing dynamic.”[10]

Predicting Gentrification

In 2002, the Northeast Minneapolis Arts Association (NEMAA) and the Arts District Committee published the Arts Action Plan.[11] The Arts Action Plan acknowledged that Northeast Minneapolis was an economically desirable location, but it also had the potential to spur business development, tourism, and investment for the City. Northeast was primed to receive an influx of investment and become populated with high-end retail, office space, and upscale housing which could increase prices and push out former artists (e.g., similar to the SOHO district in New York City). NEMAA and the Arts District Committee wanted to prevent the “inevitable” consequences of gentrification through the arts, which often displaces long-term artists by making strategic plans to try and protect the artist community.

In 2003, the City of Minneapolis designated a portion of Northeast closest to the adjacent downtown area as an official Arts District.[12] Illustrating the economic growth potential of the Northeast community as an Arts hub, the 2013 and 2015 Minneapolis Creative Index Reports confirmed that the Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington area was ranked the sixth most creatively vital metropolitan area in the country.[13] The Creative Vitality Index “tracks and compares the creative economy regionally and nationally as a significant driver of economic growth and a key factor in an area’s quality of life.”[14] NEMAA’s Arts Action Planning Committee was accurate in anticipating that the City of Minneapolis’ increased desire to support economic growth and investment in Northeast Minneapolis would in fact change the face of the commercial and residential characteristics of the neighborhood and push out long-term resident-artists themselves.

The Definition of Creator: A New Type of Maker

In addition to increased economic growth and commercial investment, a gentrified Northeast has opened up a space for all that are artistically inclined to benefit from the idea of an artist place and space. Our resident stakeholders described a tension between long-term resident-artists who typically self-identify as “raw” artists that produce very few products a year at higher prices versus those artists whose work can be mass-produced[15] at a lower cost in a shorter time frame. This tension highlights the ways that the creative economy enables different forms of art-making to become predominant and profit, expanding who is determined to be a marker. Those artists that live to produce a small number of original art pieces are feeling squeezed out by the art makers that can produce products in bulk to meet the needs of an ever-increasing tourist economy.

“I'm so narrowly focused only in the fine arts experience. So I'm only interested in that. And so I tune out a lot of the rest. But then, they got the new technologies coming at us. Like all the digital work and everything like that. So they got all this new set of tools…I was a big advocate of pluralism. The idea that everybody could be a part of it. Let’s be inclusive. Now, I live in it… But I started it with my big mouth to the 70s because everybody was, "Oh, yeah, man. Anybody-- If you’re painting the trees or painting on the trees, doesn't matter, right? Everything goes. So now we have no rules.”[16]

Half of our community stakeholders identified an influx of digitized artists including design firms, architecture firms and the tech industry. According to stakeholders, the trendiness of creative place making has drawn the interest of those digitized artists that can afford higher rents and increased costs. For some the commodification of the creative economy simply warrants a different approach to the work in order to survive.

"Everybody's trying to grab and pull the money out of somebody else's pocket. And some people are going to-- okay. If you look at the people in here… Sarah is a painter. She also drives up to Superior, Wisconsin and does murals. She rigged up a deal and they have these gallery openings that she's arranged. And I think she probably gets maybe 20% of it for hanging the work and picking the artists and working with them. And I think so far in the last year, they sold $50,000 in the condo building of art. So this is a new creative way to make an income so that you can do what you love to do. So, again, it's like any other business in America. Surviving means something different. And the younger people will… share a space like from here to that outside wall. And they have huge work, right? Three of them. Now, there's other people that wouldn't. They got more than that because they grew up in the old days downtown. And they would never [share]. Never. Because their egos are in the way. And these girls are out, you know, they're out there just running their butts off, you know, making it go and doing and finding other work or whatever they need to do to make it go.”[17]

The creative economy in Northeast Minneapolis has placed artists and art makers in a position where they are not only having to think about the authenticity of their work, the form it might take, and the best material conditions needed to produce it, but the ability to be competitive in a market that continues to expand our definition of art.

“One of the things that does have to be recognized, many of the brewers, in particular, want to be part of a continuum. They want to say I'm a creative person. I make it with my own hands.”[18]

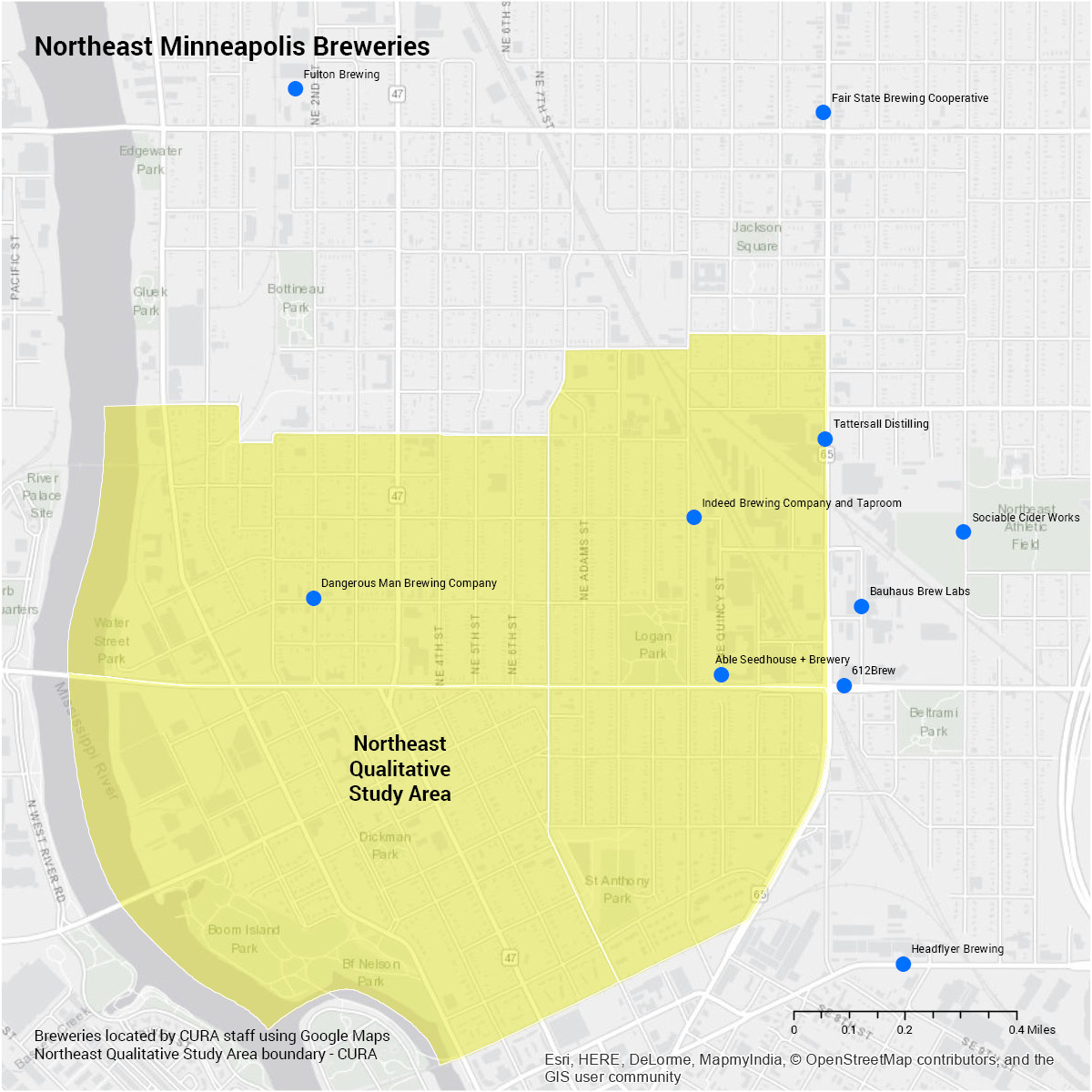

Brewers and the presence of breweries in Northeast Minneapolis is prime example of the ways that creative place-making has ushered in a new type artist culture. Since the Surly Law was signed in 2011, breweries have been able to open taprooms and sell beer out of the breweries.[19] They too, once started from humble beginnings in someone’s basement or another’s garage, aiming to build a profession around working with their hands and they have proven to have one of the most successful business models in the area.

“When the beer licensing changed the entire dynamic of the entire Twin Cities, Northeast was hit the hardest…[It had] something to do with the Surly bill. That's what they call it. So they could actually brew and sell their own alcohol was a big scenario on how this works. And it seemed overnight that we hit 12 breweries in Northeast Minneapolis.”[20]

In the last six years, Northeast Minneapolis has become home to the city’s highest concentration of breweries in the state. Northeast, from an investment standpoint, now has an exchange value based on the cultural capital that the trendiness of a designated arts district brings and its close proximity to downtown. Anyone that is a “maker” with a good business model that can mass-produce can likely benefit. With the introduction of a new artist economy has come new residential demographics, high demand for housing, and the local and national tourist looking for a bit of culture and experience.

The Secret's Out: Creative Placemaking Brings New Residents and New Costs

“Late 14, I want to say. Okay. yeah, it's gotta be the 2014, and then, at first it appeared that it was always a lot of young professionals, but then we started seeing older couples coming in here who had lived in the suburbs for 20 years and they were like, ‘I couldn't handle it, I'm back’. And they're now working out of their homes or they're doing kind of consult work.”[21]

…

“I've seen mostly recently a lot of young people, millennial people, moving in and not surprisingly they make a lot more money than I do. I'm retired. So, I'm kind of in that phase where you look at your money and you think, will I be able to live here in the coming decades? If I'm lucky enough to be able to do that. And I treat my money differently now because of the cost of living here.”[22]

All of our community stakeholders describe Northeast Minneapolis as a place that was once the city’s best kept secret, but shifting residential demographics and affordability concerns in the last decade have caused many to relocate and others to grow increasingly afraid of their prospects for staying in the area in the coming years. An increased presence of hipsters, suburban empty nesters, and young professionals was frequently cited amid detailed descriptions of a housing market that once had a myriad of vacancies to one with very little if any.

“I was looking on Craig's List 10 years ago when I first moved down here. There'd be like three pages of places in northeast to rent and I just went around and picked the one I wanted. Now if you are not one of the first people to call when that listing goes up you don't even get a call back. You have to be on the ball. You have to have your application ready. Like you didn't have to have an application before. You just walked in. You talked to the person. They said, ‘You're cool. You can live here. When do you want to move in?’ ‘Ah, like three months.’ ‘Cool.’ It wasn't a big deal. Like, no, I need you to move in now. So like now if you've got to move sometimes you have to pay double rent. And I can't afford to pay double rent, come on.”[23]

…

“That [affordability] changed probably about three years ago. I noticed a huge skyrocket. Because I wanted to move and kind of just move. When it became apparent that I couldn't, then I started getting pissed off -- and then I started noticing the changes. And then some of my neighbors started talking about taxes going up for them and the city doing some reassessment to just kind of, dumb stuff. Like the bicycle lanes. Bicycle lanes send me into a murderous rage.”[24]

…

“I've been gentrified out of six buildings. Not all Northeast, but still, a bunch of them. A lot of the art buildings are already gone. A lot of the professional artists are gone. Two years ago, I left. I still live in Northeast. I still live in this district. I still participate in this arts district. [A friend] has me as his artist in residence. But I no longer have a studio here. I moved my studio an hour and a half away to rural Wisconsin.”[25]

Every residential stakeholder interviewed was compelled to share a vivid story of the challenges that they had to face in both seeking artist workspace and residential housing leaving many questioning their future in Northeast Minneapolis. Some shared the exact cost differences they and their customers have encountered.

A two-bedroom apartment used to be $850 ten years ago and now it's $1,250. So, the house that I'm living in now in Bottineau, they want to put it up for sale because the value went from-- I think the mortgage is for $180,000, now it's valued at $289K. It's $100,000 they made in seven years. It's a huge pile of money. For seven years of owning a house! So that value of other people moving in that have more money, that can afford these places are causing the value of the property to rise. So, then people that were here already, I mean it's just-- that's the textbook gentrification. All of a sudden, I can't live there because that house is too valuable for me to live in now.[26]

...

“It's more blatant now. Now it's not even like you get the notice, you know, after so long. They were just very upfront about it. The rent's $1,650, and it's not even a full year from now. Eight months from now, it's going to up to $1,850. Well, what's the logic in that? What's happening around here, you know, economic-wise, that wants you to bump my rent up in less than a year to $1,850? What's happening?”[27]

…

“I think that apartments, if I look at my customers, you used to be able to get a one or two-bedroom apartment here for $850. Or a duplex. And now you're probably looking at $1600 to $2200. The average new-built condo studio is eleven. And a double is probably 22. That is absolutely insane.”[28]

A place that was once fairly deserted at night, full of squatters in unregulated warehouses, a reservoir for the homeless, and a place that many long-term residents-artists called home has now become prime real estate for a younger trendier group of hipsters and young professionals looking to spend their money in vintage shops and craft beer bars. Investors have jumped on the opportunity to convert once abandoned and dilapidated warehouses into upscale restaurants, breweries, and trendy destination spots, which has led more young professionals and empty nesters back into the area to enjoy the “culture”, food, bars, and close proximity to the central city.

Is It Really Inevitable?

The consequences of creative placemaking for Northeast Minneapolis has shown uneven effects between the rise of new population of empty nesters and young professionals and long-term residents, business stakeholders, and artists. Our interview participants described the rise of an art making class that has the ability to mass produce their work, unlike others before them, that fulfills the consumption patterns of a new affluent class of residents, tourists, and hipster enthusiasts as a defining outcome of a gentrified Northeast. The rise of a new creative class has ushered in drastic changes in housing and rental costs that are leaving many unsure of their ability to remain in the community and for others has forced them to seek live/work space elsewhere. The Arts Action Planning Committee anticipated the “inevitable” consequences that creative placemaking could have on the Northeast community in 2002 and now in 2017 members of the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District Board are in the process of initiating a second Arts Action Plan to assess what the current data tells them about where the Northeast community is at now. If nothing more our qualitative data analysis shows that much of what the first Art Action Plan feared is now a reality for many long term residential and business stakeholders.

[1] NE #12: White, male, renter

[2] NE #11: White, female, business owner

[3] Of the 13 residents and business stakeholders, 6 represented Logan Park, 5 from Sheridan, and 2 from St. Anthony West; 10 identified as White, 2 as Latino/a and 1 as Black; 7 males and 6 females; 3 homeowners, 3 renters, 2 long-term residents (10+ years) and 5 business owners.

[4] NE #7: White, male, business owner

[5] NE #9: Latino, male, homeowner

[6] NE #12: White, male, renter

[7] NE #9: Latino, male, homeowner

[8] NE #2: White, male, business owner

[9] NE #9: Latino, male, homeowner

[10] NE #12: White, male, renter

[12] The Northeast Arts District is bordered by Broadway Avenue, 26th Avenue, Central Avenue and the Mississippi River.

[14] See footnote #13 for links to report

[15] Art that can be mass-produced includes work that is produced in a high quantity or at a more rapid pace than some of the fine art mediums.

[16] NE #12: White, male, renter

[17] NE #11: White, female, business owner

[18] Ward 1 Councilmember Kevin Reich

[20] NE #1: White, male, business owner

[21] NE #8: White, female, business owner

[22] NE #13: White, female, long-term resident (10+ years)

[23] NE #4: White, male, long-term resident (10+ years)

[24] NE #5: Latina, female, renter

[25] NE #9: Latino, male, homeowner

[26] NE #4: White, male, long-term resident (10+ years)

[27] NE #3: Black, female, renter

[28] NE #8: White, female, business owner