Community stakeholders we interviewed in South Minneapolis feel as if the slow process of demographic and infrastructural change that has taken place in our study area has resulted in many being priced out, pushed out, or alienated. The story of community change in South Minneapolis is just as much about mobility and access as it is about the ways that demographic and infrastructural change follows patterns of racialization that privilege some while neglecting or displacing others. Each neighborhood we studied has experienced a shift in racial and ethnic diversity and a cycle of change in business ownership and investment that is indicative of the city’s historic disinvestment in the study area. Key stakeholders have described increased levels of anxiety as they have noticed their local neighborhoods or blocks changing “overnight”. As long-term community stakeholders in South Minneapolis continue to witness an influx of young white families, rising housing prices and outside investment, which reportedly feels inaccessible and uncharacteristic of the community, the fear of the “Uptowning”of their community may become a reality. The following interview analysis provides a snapshot of the narratives shared by 11 residential and business stakeholders in the Bryant, Central, Corcoran, Phillips East, Phillips West and Powderhorn Park neighborhoods in our study on gentrification.

Visit the Minnesota Compass profile for this area

Ripe for the Picking: The Fear of “Uptowning” Our Neighborhoods

“Once there's half a billion dollars of transit and bridge investment right next door [at the intersection of Lake Street and 35W], this property [Phillips West] will become too valuable to remain this low level of residential. But hopefully we've held it long enough that there is enough of a real rooted community right around here, that won't just be pushed away and this won't be the next Uptown…”[1]

…

“So, I think the greenway is a perfect example if you look at it from Uptown, of what the people who started the greenway wanted to see, meaning all that white high-end high-rises moving along the greenway …They wanted to develop an expensive high-rise here, and the East Phillips neighbor association fought them and bought the property from under them, and they built low-income housing. And that went up maybe two, three years ago. So that was a big push kind of like, ‘Wait, no, you're not doing that here,’ but it was just a clear example of what the greenway–the people that were starting [the] greenway, I think, consciously or unconsciously were thinking what was going to happen was that white flow or that gentrification flow from Uptown would get here.”[2]

…

“Well actually, I first moved to the Twin Cities in '96. Uptown was this really cool eclectic mix of like small business owners and really interesting. Like ethnic and just cool little stores. And now it's like the Apple Store and Victoria's Secret and like just all this crap. Like even like Urban Outfitters and like faux interesting stuff that's super cultural appropriation [laughter]. You know that larger businesses are pretending to be these smaller businesses. And I can see us going that way, just off the backs of artists. And because we're such a vibrant artist community, it could easily end up like that. We're just kind of ripe for the picking because, I mean, Powderhorn's an amazing artist community.”[3]

When the 11 community stakeholders[4] in Phillips West, Phillips East, Powderhorn Park, Corcoran, Central, and Bryant in South Minneapolis reflected on the neighborhood changes they have experienced they often described their fears in terms of the impending “Uptowning” of their neighborhoods. To “Uptown” their neighborhoods in this context means different things to different community stakeholders. The most common explanations used to describe this phenomenon was the influx of young white families buying homes in historic low-income communities at prices never seen before or concentrated business development in once neglected urban corridors that bring businesses that are not characteristic of the neighborhood itself.

“Now on that corner, there is a $20-a-candle - somebody just told me about this - candle store now, right across from Pillsbury House. And so, it's an interesting kind of a hipster mix. And I'm not 100% sure how I feel about it. Like, I'm a little bit concerned we're going the way of Uptown and what that means as far the people that that's going to bring into the neighborhood that's going to shop here.”[5]

…

“…there are businesses in the neighborhood that are getting targeted as gentrifiers. That’s a new development. So the candle shop actually had four of their windows busted out I guess and tagged as gentrifiers and all sorts of stuff. And I don't wish that on anybody because as a small business owner, that really sucks. And you should also have an understanding of the neighborhood that you're coming into.”[6]

“Uptowning” is a verb that most community stakeholders associate with developers and city officials moving away from supporting small mom and pop shops and building affordable housing to rapidly developing denser market rate housing, increasing property values, and new high-end specialty shops. For the purpose of our brief analysis we will focus on two major themes of community change that were shared consistently by all of the community stakeholders we interviewed—the influx of a new residential population and concentrated business development.

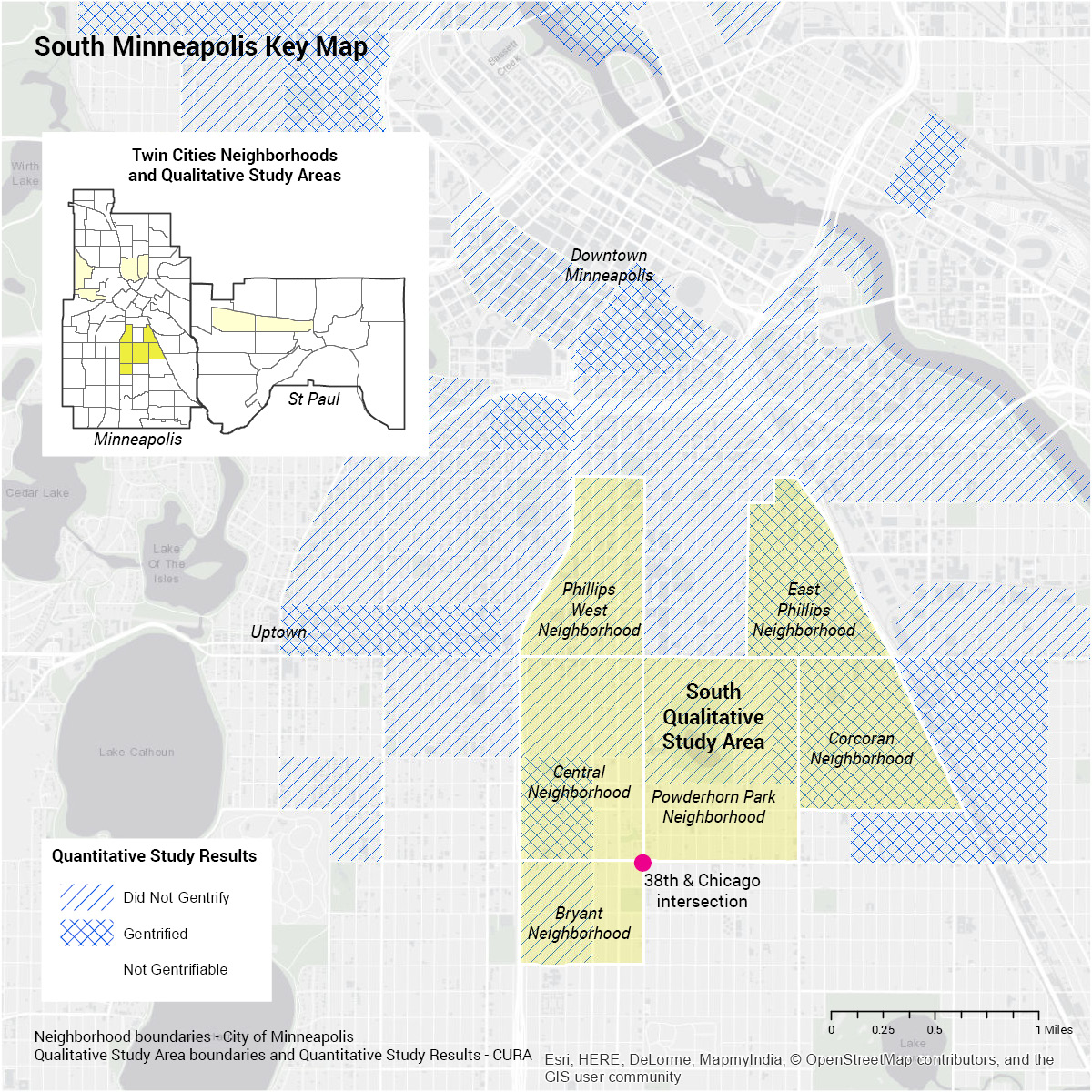

The five neighborhoods in South Minneapolis we studied make up the largest geographic area that CURA analyzed in its gentrification project. For the purposes of this snapshot, particular areas in this cluster, such as the neighborhoods that intersect at 38th and Chicago including Bryant, Central, and Powderhorn Park, are given more attention in order to provide an illustration of the overlapping, yet distinct histories. These themes will include racial and ethnic residential population change and economic development patterns that have left major corridors filled with vacant or dilapidated properties defining this area’s history of disinvestment and the transitory nature of its residents. For example, while the area along E 38th Street was once a thriving historic black business district, later devastated by the construction of interstate highway 35W and the closing of Central High School, many Latino immigrant families in search of affordability have repopulated communities such as the Central neighborhood. Although this history of disinvestment might have prompted some to seek opportunities and networks outside of the neighborhood, it has inspired many more to lay down their roots and invest in the community in hopes of ensuring that all can benefit from neighborhood change.

Are We Losing Our Racial and Ethnic Diversity?

“What I'm seeing is more white people in jogging attire jogging through my neighborhood. A lot of my homies-- one night, we were having a fire. It was all POC [people of color] dads and we were just having a fire. It was getting dusk and we were like, ‘You know if we were running right now, there'd be some questions [laughter]’."[7]

…

Well, but the other thing I'm seeing, at least in my area [Central] that I’m talking about, but over as you go other places there certainly are a lot more Caucasian, European people moving in, than there were. And [Caucasian and European people are] not leaving and not avoiding. I mean, I can remember telling people where I live and they'd say ‘You? You live there?’”[8]

…

“Well, we have a lot more Caucasians that are in the area than there used to be about four or five years ago. All of a sudden there's this influx of the - what do you call it - I would say 20 to 40 with new families and stuff that are moving in the neighborhood.”[9]

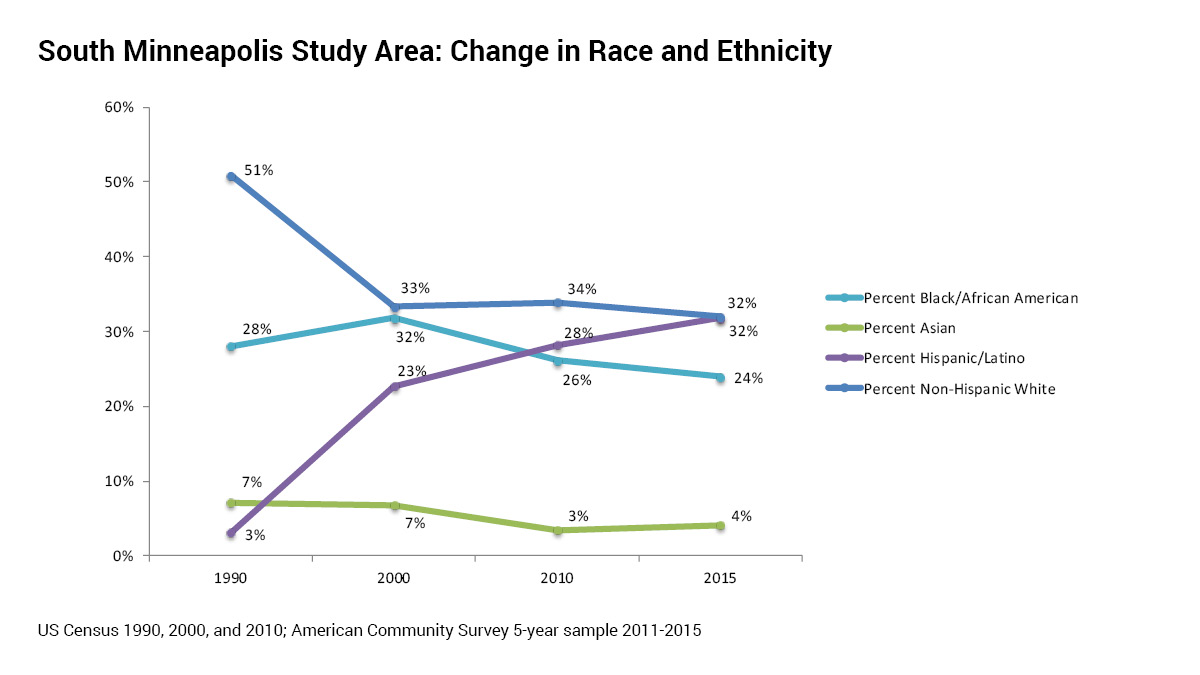

Our community stakeholders use multiple terms to describe the shifting residential demographics they are seeing in their neighborhoods. However, almost all our stakeholders associated shifting racial demographics with the increased presence of whiteness in parts of South Minneapolis that white buyers had historically avoided (e.g., S#6 quote). For residents of color to see white joggers out late at night reinforces for them the imbalanced racial hierarchy that criminalizes some while absolving others (e.g. S#2 quote). Or the sheer quantity of new white residents created anxiety for long-term residents leaving them to question the future of their neighborhoods (e.g. S#3 quote). The data does not suggest that a complete turnover of racial and ethnic diversity has taken place in our five South cluster neighborhoods. However, all of the stakeholders we spoke with described the influx of new white neighbors with some level of anxiety as they have noticed their local neighborhoods or blocks changing rapidly—for better and for worse. These perceptions of long-term residents can pick up trends before they show up in census counts or at scales smaller than the census tract level. Thus, they constitute an important supplement to what we see with the quantitative data.

“Well, the neighborhood got better, I mean, where we came from, about seven years ago. You know, the neighborhood got better, you know with businesses coming in. Other peoples coming in, you know? The whites were moving out, now they are moving back in. So, to me, the neighborhood is growing. I don't see a lot of violence no more-- hear a lot of gunshots and gang members and all of that.”[10]

For some community stakeholder’s, growth is not necessarily a bad thing, but the fact that growth and investment seems to follow the mobility patterns of white residents with resources has created an unsettling tension among residential business owners. Some say they can see value in the presence of new potential customers, but they also fear that those existing residents (and customers) that made them want to stay in the area will be pushed out or new consumers with different tastes and higher incomes could cause their businesses to suffer.

“I made the neighborhood a promise that I will not go nowhere and I'm doing everything in my power to do that because I always broke the promise, but this promise, only way that it will be [broken]… I move out of here, that I had to move up out of here. But other than that, they gonna see my face until I get old and grey.”[11]

The mobility patterns of white residents, whether it is where they are concentrated and/or where they choose to move, has become an indication for many city officials and planning practitioners locally and nationally of the growth and safety potential of any given neighborhood. These mobility patterns and subsequent changes in neighborhood demographics make it challenging for any business owner of color to thrive in neighborhoods becoming populated with new affluent white residents. High concentrations of people of color within under-resourced inner-city neighborhood have been characterized as a determinant to growth whereas the actual problem is not that people of color are living in close proximity to one another, but rather that when redevelopment funds are invested in local neighborhoods they do not typically follow the original business owners in the ways that they do affluent white residents.

Similarly, another community stakeholder maintains that a lack of affordable, Section 8 housing options for low income communities of color in our South cluster neighborhoods is pushing people of color outside of their desired communities of origin into inner and outer ring suburbs. According to this view, the outmigration of some families using Section 8 vouchers has made way for the in-migration of a different set of households.

“Yeah, Section 8, the vouchers and stuff are now good for places like Woodbury and Brooklyn Center. And then when you get people way out in those areas, then they can't have jobs down here, because the bus stops running at a certain time. So then once you get them out there, they're stuck out there. I see that happening as well where more people are being moved that way and then as they move out, then the other group of individuals, the young business professionals, the young families, then they start moving into this area.”[12]

The community stakeholders described the loss of low-income populations of color and, how in the process, these populations are being pushed further away from accessible public transportation and jobs in order to secure affordable housing. This has, in turn opened up the housing market in the central city for a more affluent class looking for the convenience and culture of an inner city urban lifestyle.

As stakeholders describe their experiences with shifting residential demographics, they are always already talking about race and the politics of ownership, especially as some residents wrestle with whether or not gentrification is a good or bad thing for them and their neighbors (old and new).

“There was the apartment building directly across the street. It's probably the number one marker of gentrification that I could see. That apartment building for years, probably 15 years, was really horrible. It's 19 units, and it’s efficiency units, so just was horribly mismanaged. And just gang activity, and people just hanging out at front and screaming and shooting, and just all sorts of stuff. And then a new owner took it over, and now it's all sorts of hipsters and people with bikes carrying their bikes in [laughter].”[13]

This particular community stakeholder created a racialized contrast between former renters who were living in mismanaged “efficiency units” that were filled with “screaming” residents that were assumed to be members of a “gang” to her new young “hipster” neighbors with bikes living under new management. This perspective illustrates the ways that perpetuators of disorder are easily racialized through descriptions of behavior (hanging out at front, screaming, shooting etc.,) that can have the effect of defining who is more invested in a neighborhood and who is not.

“Well, I mean there's guilt because I'm a homeowner. And so I probably will be fine. You know, that sucks in so many ways that I'm able to watch this and be like, "Well, I'll probably be fine." It sucks because you can see it coming. It sucks because I will benefit from it. It sucks because I know there's a part of me that's like, At least like, you know-- Oh, there's not as much trash [laughter]. You know? That apartment building's better. You know, the uncomfortable other-- you know, isn't as prevalent. And that's that. I don't like that part of me. And knowing that there has to be a space for the people. They have to go somewhere. And it doesn't make any sense that they have to go somewhere unsafe and that they have to start the cycle all over again. Cleaning up the next place. Like, that's just exhausting, just even thinking about it. So anyways. (Crying)”[14]

When this community stakeholder began to cry and discuss the privileges she associates with homeownership she illustrated the internal tension she felt as someone who would “probably be fine” compared to the experiences of the “uncomfortable other” (former renters) who because of the process of gentrification had been displaced into a community that this stakeholder presumed was unsafe. This community stakeholder was openly wrestling with the guilt that shifting residential demographics has had on her relationship with the community. This was exacerbated by her own unsaid fears about how demographic and infrastructural change follows patterns of racialization that will benefit her while neglecting or displacing others.

There is clear tension between the ways that different stakeholders describe their relationship to these patterns of change. Whereas, S#7 made a promise to historic black residents to stay in the neighborhood with the hopes that his business can grow and thrive with those same residents as major benefactors all while he sees the demographics changing, S#4 had developed an association with residents of color to a mismanaged property across the street from her home that once repopulated with hipsters changed the neighborhood for the better. These different perspectives not only raise the question of whether or not gentrification is a good or bad thing, they illustrate how race, class, gender, and mobility options might influence perspectives on the phenomenon of neighborhood change.

Concentrated Business Development in the Gentrifying City

Community stakeholders are not only cognizant of the influx of a new residential demographic as the housing and rental markets continue to shift in price, but they are also alarmed by the increased levels of business development that coincides with the closing of historic businesses and the displacement of important cultural institutions.

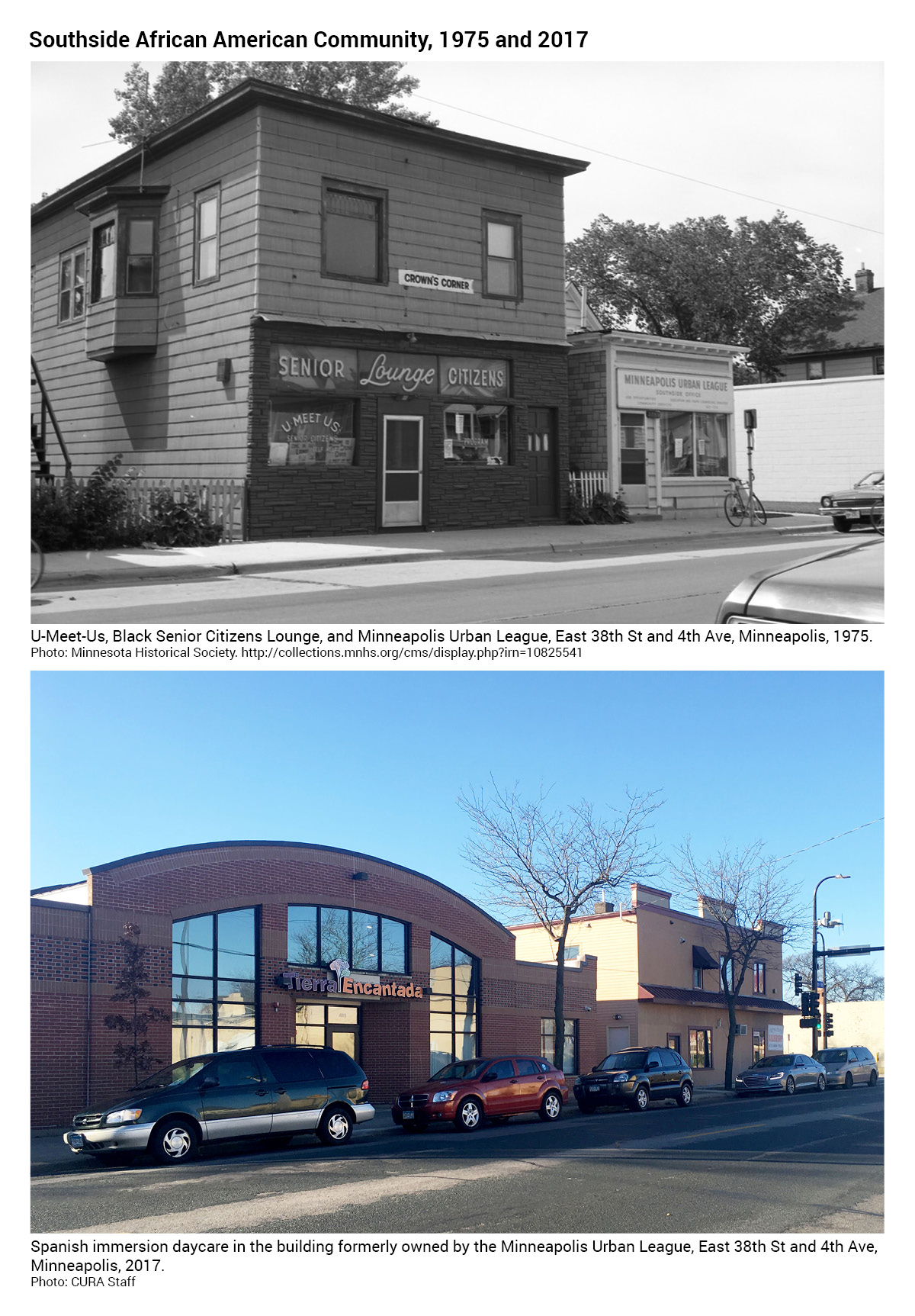

“We have a lot of stuff going on, a lot of the African American businesses are closing, there are some that are still here. Our center is one that's still here. Smoke in the Pit is here, but the Minneapolis Urban League is now a Spanish school.”[15]

For those new businesses coming in, while the historic businesses struggle to stay alive, most of our community stakeholders described the new businesses as not being characteristic of the neighborhood itself and perhaps shifting with the repopulation of the area. The Blue Ox Coffee Shop, for example, opened in 2011, near 38th and Chicago by a middle aged white woman from a surrounding suburb. Once described by the City Pages as a place for “Coffee snobs to geek out,” community stakeholders stated that they believed this business was uncharacteristic of the area. After complaints of high priced coffee and pastries with an unwelcoming atmosphere, this business closed and later reopened under new ownership.

“Blue Ox. When they first moved in trying to do something different in the neighborhood. And I tried to talk to the owner at the time of Blue Ox, to let them know things to draw the neighborhood in, the people that have been here forever. And they really didn't buy into that and they didn't last very long because of their product and the area and what people are used to and the price.”[16]

…

“The Blue Ox. Yes. They were making single drip coffee. Five dollars a cup. It was like, this is really not that community you guys, but good luck.”[17]

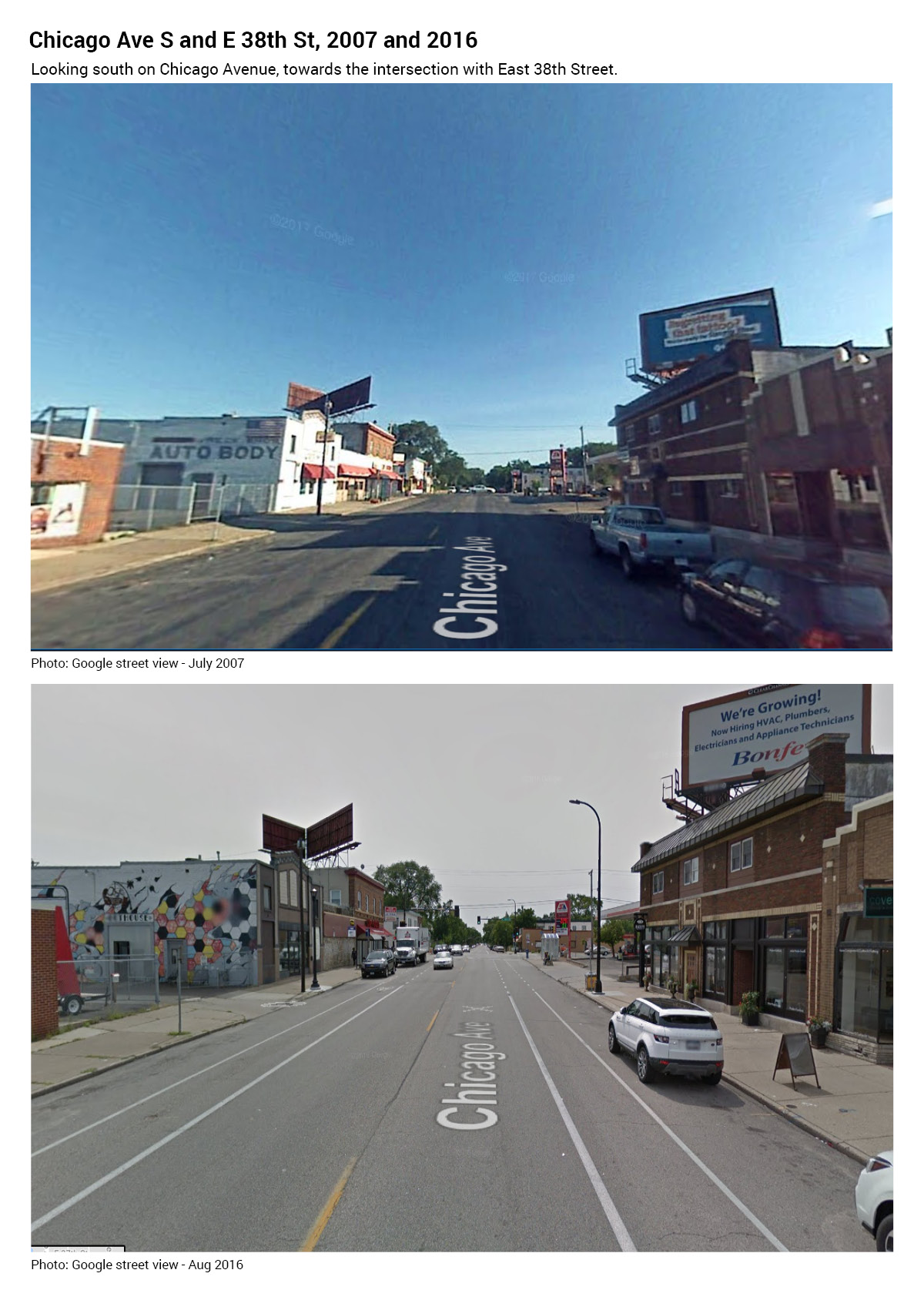

All stakeholders described the increase in business investment in places that have historically lacked it as a sign of gentrification. Most of our community stakeholders focused on developments along the East 38th Street and Chicago Avenue corridors, which brought not only new businesses, but increased interest from investors, increased leasing costs, and higher priced goods and housing.

“I get called a lot of time, from individuals, trying to find space to rent in this neighborhood. Because I was also the chair of the 38th & Chicago Business Association, so I get calls. I still get some things on my email about that, people wanting to move in the area because they're really interested in getting into the space because the city is really ramping up.”[18]

…

The other [sign of gentrification] is even in my business I see a lot of other-- we've had that space on 38th Street for, goodness, over 25 years. I get calls just about every month somebody wanting-- "oh, you ready to sell your building? Da, da, da, da, da?" Because they want the space.”[19]

Local businesses are deeply engrained in the communities that they are in and when neighborhoods undergo meaningful changes in the economic landscape, one would expect that local businesses will feel the effects. The community business owners that we interviewed have not been displaced (as of yet), but are either in fear of being displaced or are currently feeling the pressure from outside investors that make them fear what changes might come with an increased level of interest in the area.

One business owner we spoke with described his tireless fight during the last decade to stay in his building as he had to work with a landlord that refused to make certain repairs and upgrades, because he did not see it in his best interest to do so. This left him fearing the day that he would get evicted especially after he took it upon himself to invest a large sum of his own money into a building that he did not own.

“Well, I had to deal with a slumlord. And I had to take my retirement money, well not my retirement money, but the money that I had saved up to come in here and fix up somebody else's building and then think whether they were going to sell it to me or sell it out from under me… And I spent about 75,000 up in here when I first moved up in here. I had to re-gut this whole little old 500 and something square feet. New plumbing and new electrical and new everything. Now I own it because I fought for it.”[20]

This community stakeholder is admittedly one of the lucky few black residential business owners to still be in business and is now the proud owner of the building where his business is located. However, it was an struggle for this business owner as he found very few financial institutions willing to support his business, a situation which he says is a major challenge for business owners of color in Minneapolis.

“Well then I know they got the 2% loans down there and all of that, but the red tape that you have to go through to get the loan. You got to give up just about everything you own. They want your house, they want your car, they want your piggy bank, they want everything to put it on…. Just like the banks, the banks the same way, you know? Just because these people got bad credit back down the road, that don't mean that their credit is going to stay bad. Give these people a chance to do right and show the person that you care for them, to give them a chance. That'd be better for us to get things done, because if the bank don't give us nothing, who's going to give it to them? Because black folks weren't born with money and a lot of white folks weren't born with money either, but the ones that want to make something out of themselves, them the ones that the bank turn down. They'll give it to the Africans, they'll give it to the Hmongs, they'll give it to the white folk but the black man walk up in there, they're going to judge him. His shoes better be shining, he's got a tie on and a briefcase with just paper in it because if he don't, they ain't going to give him nothing. And that's real.”[21]

A few short blocks away we encountered two business owners like S#7 that were only able to get financial support from the Metropolitan Consortium of Community Developers (MCCD). Despite that support, these business owners had to recently run a GoFundMe campaign to not only keep their doors open, but to save their homes as they mortgaged their home to help finance their business. A family owned coffee shop created as a safe space for queer and non-gender conforming youth, many of whom suffer from homelessness. This community based small business intentionally hires under-employed queer youth and at the time of our interview had gone months without paying themselves in order to keep their business alive placing their own livelihood at stake.

“So, we opened up extremely underfunded and scrambled even to just be able to get a small business loan. And at the time I had excellent credit. I owned my house. And I mean the amount of loan that we qualified for was under $20,000 to open up a business. They would only give us seventy-five percent of it up front and my house is on it. That's my collateral. And my house is worth way more than [laughter] that.”[22]

Admittedly underfunded, these community based business owners worked to open a business to help provide a safe space for those queer youth and families that have been living in and drawn to the arts and culture of the Powderhorn community for some time. However, as they struggle to find financial support and as the price of commercial leasing spaces continues to rise, they worry about their ability to stay open and serve the interests of the underserved communities that they are committed to supporting.

How Can We Address the Fear of ‘Uptowning’?

The process of demographic and infrastructural change that takes place in some neighborhoods can leave residents and business-owners priced out, pushed out, or alienated. This process leaves many stakeholders feeling as if the neighborhood changed overnight, because once these shifts become widely recognized it can be too late. Some will have moved out, voluntarily or not, the others who still live in the neighborhood may no longer feel a connection to the people living there. For the residential business owners we interviewed, they feel as though they are in for the fight of their lives as they aim to maintain their commitment to those community members that have supported their businesses throughout the years. This does not mean that these business owners do not want growth. All the community stakeholders we spoke with want growth in their neighborhoods, but they also want to be around to directly benefit from that growth. As the community stakeholders in South Minneapolis continue to witness an influx of young white families, rising housing prices and outside investment, much of which reportedly feels inaccessible and uncharacteristic of the community, the fear of “Uptowning” is ever-present.

[1] S#9: Native American, male, renter

[2] S#2: Latino, male, long-term resident (10+ years)

[3] S#1: Female, business owner

[4] Of the 11 residents, 5 identified as Black, 2 as White, 1 as Latino, 1 as Native American, 1 as Middle Eastern and 1 declined to identify; 6 males and 5 females; 3 homeowners, 2 renters, 3 long-term residents (10+ years) and 3 business owners.

[5] S#4: White, Female, homeowner

[6] S#1: Female, business owner

[7] S#2: Latino, male, long-term resident (10+ years)

[8] S#6: Middle-eastern, male, long-term resident (10+ years)

[9] S#3: Black, female, business owner

[10] S#7: Black, male, business owner

[11] S#7: Black, male, business owner

[12] S#3: Black, female, business owner

[13] S#4: White, female, homeowner

[14] S#4: White, female, homeowner

[15] S#3: Black, female, business owner

[16] S#3: Black, female, business owner

[17] S#11: Black, female, homeowner

[18] S#3: Black, female, business owner

[19] S#3: Black, female, business owner

[20] S#7: Black, male, business owner

[21] S#7: Black, male, business owner

[22] S#1: Female, business owner