North Minneapolis has a deeply rooted history of strategic disinvestment and racial segregation. Today, Willard-Hay residents must once again face outsiders laying claim to the rights to restructure the community. Key stakeholders have identified the strategic use of historic preservation as a tool of gentrification, yet the potential consequences for long-term residents remain unspoken. Harrison residents have reported similar experiences of unbalanced power dynamics regarding the development of the Glenwood corridor, which impacts community change. The voices at the table include members of the Harrison community, but they struggle to be heard above residents of neighboring communities, developers, and the city of Minneapolis. These dynamics leave Harrison residents wondering whether or not they will be able to remain in the community long enough to benefit from future economic growth. The following interview analysis provides a snapshot of the narratives shared by 14 residential and business stakeholders in the Willard-Hay and Harrison neighborhoods in our study on gentrification.

Visit the Minnesota Compass profile for this area

The Right to The Community

“Descriptions of gentrification as a market process allocating land to its best and most profitable use, or a process of replacing a lower for a higher income group, do not address the highly destructive processes of class, race, ethnicity, and alienation involved in gentrification. …[T]he right to the community is a function of a group’s economic and political power.”[1]

…

“And in recent years, as more and more people are walking their dogs, as the neighborhood's changing-- and there's talk about the neighborhood changing and there's this sense of feeling like people of color are being pushed out. … I have no proof of this. But there was this sense like you [White resident] were looked at more suspiciously. That there was a raising level of discomfort. And so I think when you talk about people feeling culturally comfortable in a neighborhood, as the demographics start to shift, the people who had been the anchor to the community begin to feel like, is this still my neighborhood or not?”[2]

North Minneapolis is a community whose historic destruction is about strategic economic disinvestment based on the class, race, and ethnic profile of its residents. In North Minneapolis, as in communities of color in cities across the nation, decades of economic decline were triggered by the shift in public and private investment that followed white, middle class families to the suburbs. The conditions of inequality have always been visible (made mostly through news accounts of violence and crime) to the estranged suburban onlooker that North Minneapolis is a place of violence, poverty, and dysfunction that should be avoided.

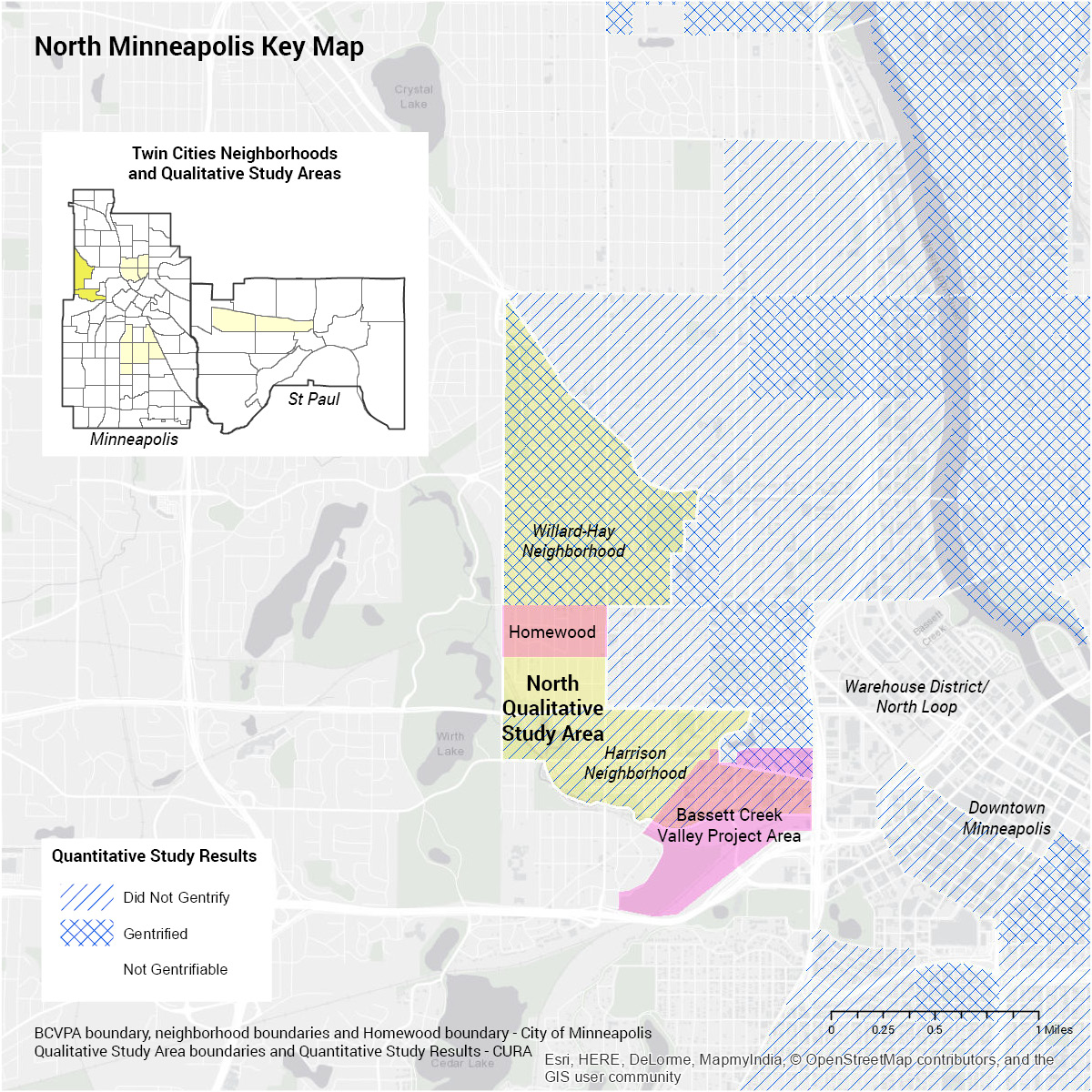

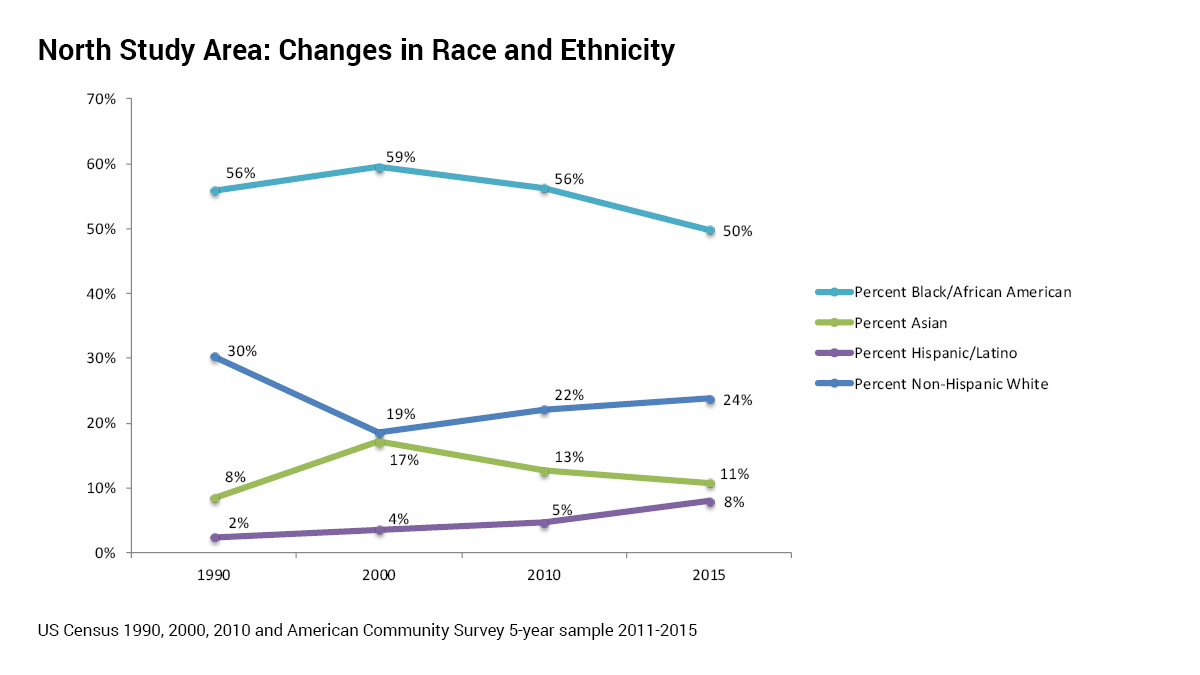

Today, rapid urban restructuring throughout the Twin Cities ensures that a community once manufactured to contain undesirable low income Black residents, is now slowly becoming attractive to a rising population of young white families. These new residents see an undervalued housing stock and a community adjacent to downtown Minneapolis that fulfills their urban living dreams against the backdrop of an increasingly unaffordable metropolis. CURA’s analysis of housing and demographic trends in Minneapolis and Saint Paul identified the Willard-Hay and Harrison neighborhoods within the Northside as being especially subject to gentrifying pressures.

“Gentrification on its own, that definition is good - development, prosperity, increasing incomes - but what we see, and what we feel, is that those that are currently here don't get to participate in that. The increase in income, increase in value, is brought by new people being introduced to our neighborhood, versus those that are maybe in low income or in poverty being lifted out of that situation.”[3]

The Unspoken Consequences of Historic Destruction

Through our interviews with 14 residential stakeholders[4] we found that the consequences of historic destruction and the narrative of decline positioned against low income Black and Brown communities have produced a number of negative economic, social, and political structural realities, which has made gentrification possible. Primarily, who gets to define the urban agenda in North Minneapolis is now under debate, because a cultural, social, and political divide (realized or internalized) has begun to develop between new more economically affluent residential stakeholders and historic low and working/middle class residents as they find themselves vying for the right to community. This has created anxiety and fear for low and working/middle class Black and Brown families who are either forced to reside in the area, because of the historic affordability of the Northside or for those families that choose to live, shop, and raise their families on the Northside, because of its culture, politics, and its immeasurable community assets. In our interviews, we found that anxiety arises, because of the perceived neighborhood changes that are yet to come or because residents are looking at their neighborhoods and seeing concrete changes in residential demographics, infrastructure, and housing, and fear for their own ability to continue to reap the benefits of the changes they are seeing. The history of urban revitalization has shown that when major infrastructural and residential changes occur displacement typically follows.

Who is at the table, what power those at the table wield, and how specific processes of community development influence infrastructural change become repeated signs for many, without economic or political power, that they are disposable in the current processes of neighborhood upgrading.

“A lot of individuals that live there [North Minneapolis] really don't have the power or voice or see that their voice has power in requesting some of the things that they need in their immediate environment.”[5]

In short, the slow process of gentrification becomes a second slap in the face for many who understand the ways that “white flight” and urban renewal of the 50s and 60s left them and their families isolated and undervalued. For the buying power of white middle and upper income communities to continue to dictate how low and working/middle class Black communities will or won’t live has exacerbated a feeling of disposability that impacts how historic residents see themselves and the city and state's commitment to their livelihood.

“One thing that I noticed … when having a community meeting, people will stand up and say, ‘My name is XXXXX, and I am a fourth generation Homewood resident.’ They're always citing their relationship to the community and their longevity…because these people have been living here, and been having to deal with people coming in and telling them all the time, what is the new wave. And they're asserting, ‘I've been through all these waves, and you're still not going to tell me, or I still don't appreciate this.’"[6]

The unspoken consequences of historic destruction are directly connected to long term resident’s feelings of devaluation as they are continually placed in settings where they must lay claim to the neighborhood to ensure that the “new wave” does not place their needs on the figurative chopping block. Those residents typically see change happening to them rather than with them. In the case of gentrification, that change is buttressed by feelings of powerlessness especially when long-term low and working/middle class Black families do not see or feel the direct benefits in their daily lives.

“So as much as I like to see good [white] people running around and enjoying their community, you know what I'm saying, enjoying their amenities, those amenities shouldn't just come with those people.”[7]

Historic Designation as a Tool of Gentrification?

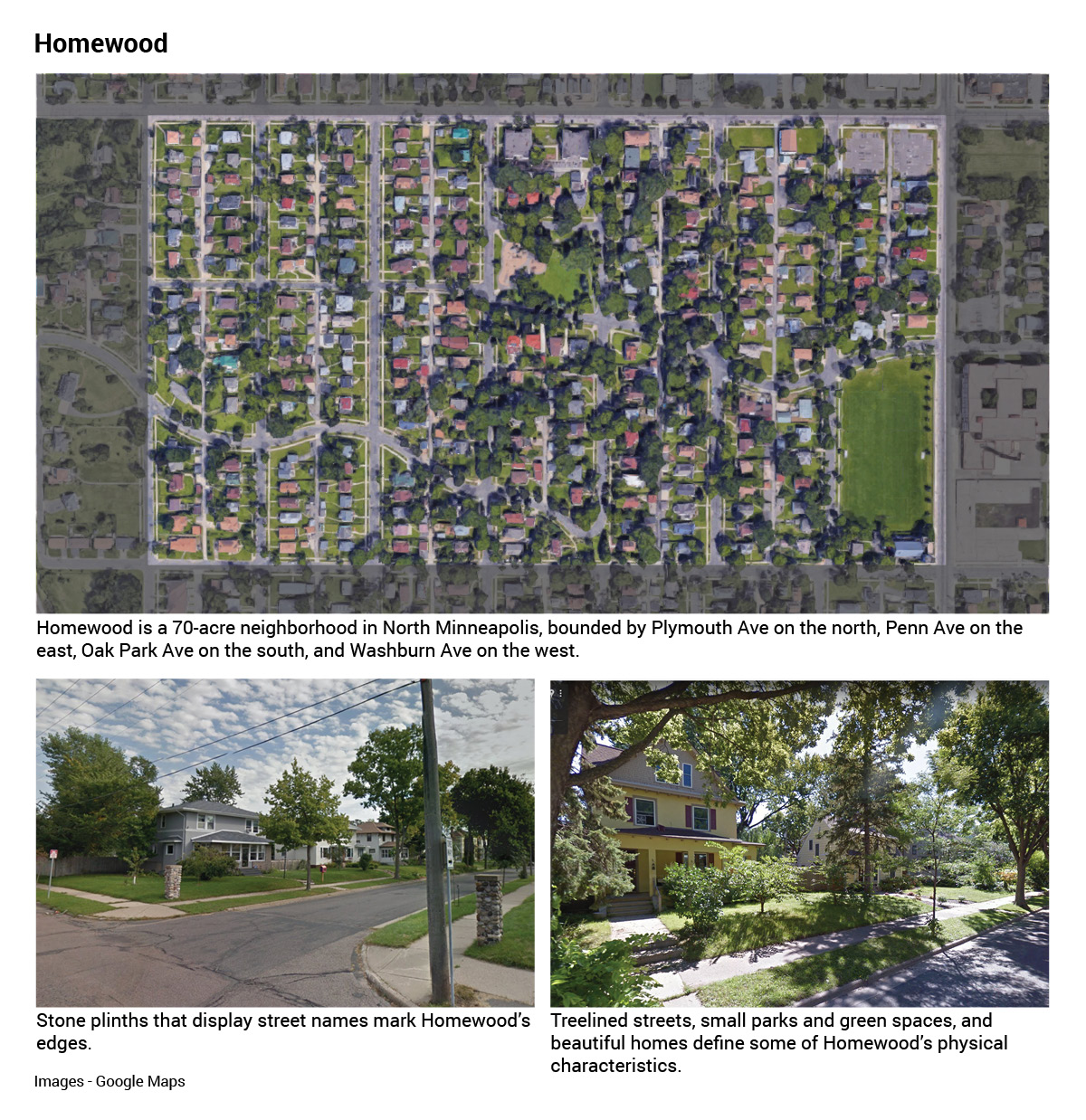

On March 7, 2016, a small neighborhood meeting[8] was organized to discuss the nomination of Homewood as a historically designated area.[9] On the one hand, residents in support of the nomination are willing to pay more in permit fees and contractor costs to preserve the distinct architectural characteristics of their homes while also preventing outside investors from buying up properties, tearing them down, and building mini-mansions. On the other hand, residents, many of whose families replaced the historic white Jewish community post 1959, are deeply concerned with current homeowners’ ability to finance the type of architectural standards these homes would require limiting their ability to choose their own contractors and select bargain materials. These residents also cited increased property values and the fear that a new type of affluent homebuyer would be strategically drawn to the neighborhood adding another layer of exclusivity to the area.

It is reported that a handful of residents, roughly 10, submitted the formal nomination paperwork, an effort led by real estate agent and Minneapolis Historic Preservation Commissioner, Constance Vork.[10] A group of Willard-Hay residents took it upon themselves to canvas the 247 properties nominated for historic designation and received 131 signatures in opposition to the historic designation status.[11]

“She's [Constance Vork] lived on the north side, further north for a while before she bought a house right over near mine for years. She's a dedicated north side person. She's a very good real estate agent, very honest and has plenty of integrity. And loves this neighborhood. So she proposed the historic designation. So she's become the villain now. She's the one who's gotten this-- people are pointing at her and saying, "She got us in trouble. She brought this up." But I think she was doing her job as a historic preservationist and as a real estate person with integrity who wanted to see these houses she was interested in preserved in some way.”[12]

According to Christianson, rising opposition to the nomination has prompted the City of Minneapolis to investigate what incentives it could offer residents if the City Council approves the nomination in October of 2017. For Christianson, this means that residents in the Homewood neighborhood will be subject to the historic guidelines for another six months. If financial incentives are put in place Christianson fears that they will be turned into a “gated community” with advantages given to Homewood residents that the adjacent neighborhoods will not have.

Well-intentioned approaches to community change can have many unforeseen consequences particularly for those who typically lack economic and political power. Historic designation has the potential to prevent the creation of mini mansions and to preserve historic housing stock. Yet, it also has the potential to create a neighborhood that can only be maintained by those with the capital to invest in the historic restoration of their homes. In this case, 80% of residents interviewed argued that a small number of politically empowered residents were able to use historic preservation as a tool of gentrification. They maintained that it is negligent to only see improvement and upgrading without seeing the potential for involuntary displacement.

“It's gentrification because nobody gave a damn about Homewood for years and years of really trying to help it, but now that it's good, solid, old, beautiful homes that could be restored, it's close to downtown, it's right on the parkway. Beautiful space. All of a sudden, there's this interest to make it an elite neighborhood that would take it out of access to the existing people and people that live in the neighborhood...So it's forcing a rapid change of the economics, and it's going to displace people. And to me, gentrification isn't just about bringing in the gentry but it is displacing the people who have been here and been part of the community.”[13]

The historic preservation initiative in Willard Hay is an example of an accelerated process of community change that could have lasting effects on the community’s composition at a time where rapid private investment and increasing housing prices are making it impossible for many low/middle income families to continue to live in the Homewood area of the Willard-Hay neighborhood.

Stakeholders that are not long-term members of the community often heavily influence decision-making processes in neighborhoods such as Willard-Hay. In many cases, even though their intentions may be well meaning, they may often be triggering social, political, cultural, or economic dynamics from which they are poised to reap direct benefits. Existing residents are, in turn, typically shut out of these benefits [physically, culturally, and economically].

Divides at the Table

“You go across the [Glenwood] bridge [between Bryn Mawr & Harrison neighborhoods], and all of a sudden you're in North Minneapolis and the housing values are 150 K less… It's like I'm in South Korea, and then all of a sudden I'm in North Korea. It doesn't make any sense to me. And I can't see how that doesn't have a really large impact on the communication that folks have. Because they are neighbors…But there is such a dividing line with that creek… part of what I think about is yes, we have this kind of historical, layered perception of what North Minneapolis means to everybody. And I grew up in the 90s, and "Murderapolis" was the moniker for-- and predominantly because of North Minneapolis and all the violence that came out of there. It doesn't feel to me like that's actually real. It's perception. It's not reality. And how the perception comes into reality is in housing values and in equity in people's bank accounts.”[14]

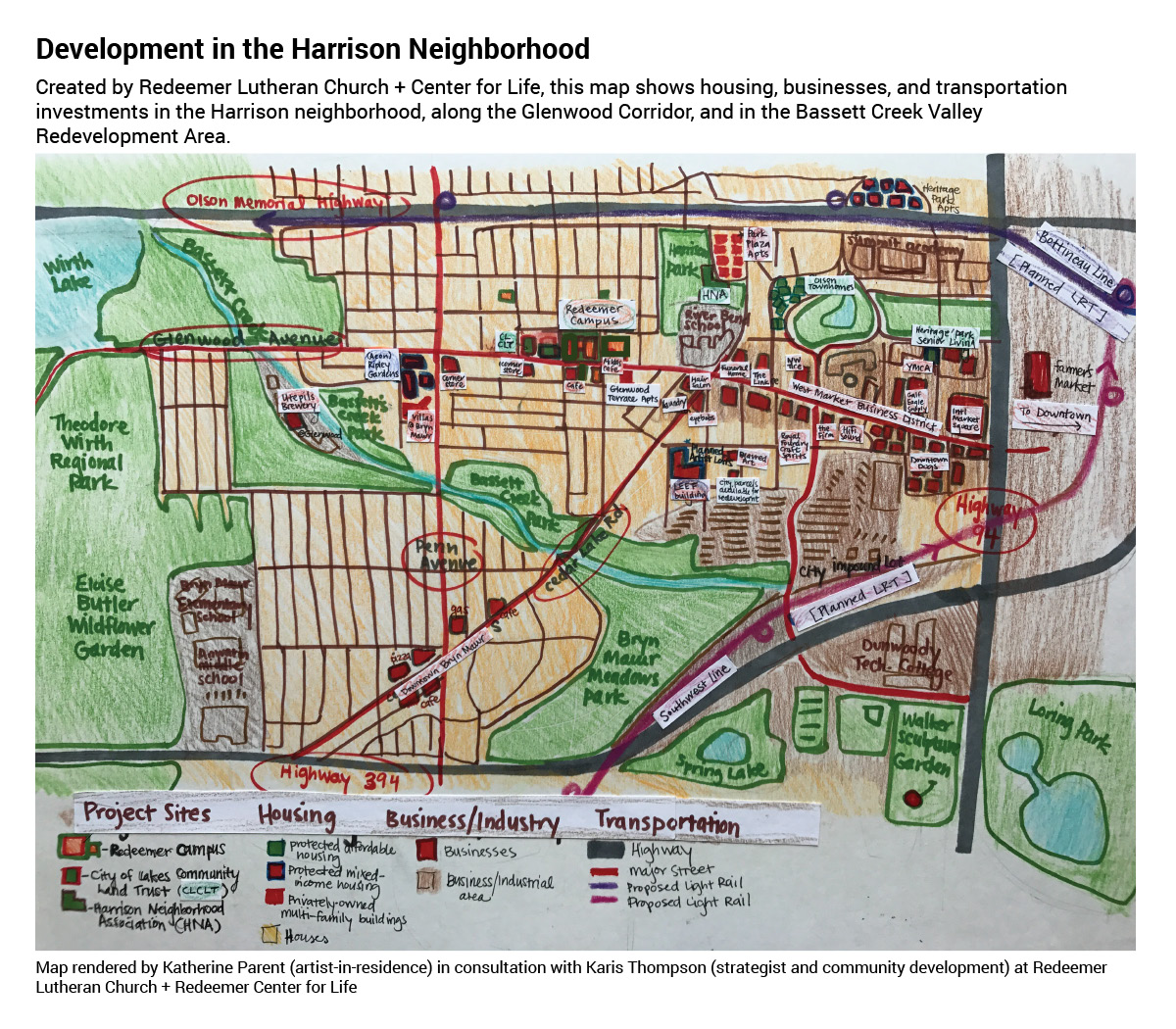

The Bassett Creek Redevelopment Oversight Committee (ROC), a committee of residents, business owners, city appointees and developers, was established in 2000 by the Minneapolis City Council followed by an 18-month strategic planning process that would create a master plan for the area and locate a master development partner. The Bassett Creek Valley project area includes two distinct neighborhoods [Harrison & Bryn Mawr] with sightline views of downtown Minneapolis and the Twins Stadium. Harrison residents are acutely aware of the fact that being sandwiched between the North Loop downtown business and entertainment district on one side and the affluent Bryn Mawr community on the other makes the Glenwood corridor a prime location for cheap investment and easy access to the attractions of downtown.

The developers are not necessarily displacing people by tearing down existing housing stock, because there was very little housing in the corridor prior to development. Instead, the fear is centered on the rents increasing and the rise of a new demographic class creating a culture of belonging that will not include low-income families and their needs. These fears are reaffirmed for these residents not only by the proposed blue line light rail extension along Olson Memorial Highway and Van White Boulevard, but also by the recent opening of a brewery [Utepils, 2017], a specialty eyeglass shop [Eye Bobs, 2016], high end wine shop [Henry & Son][15], an advertising firm [KNOCK, Inc., 2010] and a newly proposed affordable artist housing complex [Artspace, 2016].

“Unfortunately, gentrification is a double-edged sword. When you come into a neighborhood, especially one where people are a lower income-- and in Harrison, the last set of numbers I heard was $29,000, the median income-- any development you do that improves that neighborhood is going to cause gentrification. It's going to cause anxiety. It's going to cause major changes.”[16]

There was not one person that CURA interviewed who did not want growth or who did not desire access to new amenities. However, they did not want to receive economic growth in their communities at the expense of their ability to remain in the neighborhood and benefit from access to these new amenities.

“I have enough life experience to know that transportation, light rail, changes a community radically, and over time, this is going to be a very different community because of light rail, assuming that light rail is going to happen so... And so the ongoing challenge and voice that we have as a community whether it's Redeemer, the neighborhood association, the mosque… who will benefit from the future development? Who will benefit from gentrification? Who will get the jobs? Will the current residents be able to stay here, benefit from all of that? I mean that's really the bottom line, and what's going to happen. This is a great neighborhood and a great location. It's close to downtown. That development ultimately is going to happen, and it didn't happen before because of who lived here, and the people who lived here weren't seen as-- to be primary beneficiaries of that so. That's going to be the ongoing battle is will the current residents' population be able to benefit?”[17]

When residents were asked what signs of gentrification they were seeing, they all cited the increased presence of young white families and new economic investment that did not match the historic character of the area. With new residents come investment in areas that long-term residents themselves have always desired, but which they fear they will not have a chance to experience.

“…gentrification isn't necessarily a bad thing, but the way that it happens historically is that people who purchase, land owners, to protect their investment have this framework that they have to get rid of the people who are currently there, so it's a losing proposition for current residents.”[18]

The ROC prides itself on not having to rely on any city dollars to generate, spur, or execute any infrastructural development on the Glenwood corridor. This sense of pride comes from a place of industriousness on the part of a determined group of power brokers at the table. The ROC has allocated seats for the following community stakeholders: (4) Bryn Mawr, (4) Harrison, (4) Business Owners (4) City Council appointees, (1) Mayor appointee, (1) Friends of Bassett Creek, and (1) Park Board.

“We have had no city funding at all, other than appropriate staff. We have had some marvelous, marvelous CPED folks helping and guiding. Like when it comes to zoning…Ryan Companies, for instance, I would guess spent at least three-quarters of $1 million in the various studies of land and they had Maxwell come in and tell us how much housing, or what kind of housing we could have. The only thing Ryan asked was, ‘When this plan is presented, we would like to have exclusive rights to development.’ And that ROC was more than happy to give them, and they had exclusive rights to what we call the banana…Ryan was given a seat at the table, simply because they were paying for all of that, and we listened because they gave us very good advice when it came to development.”[19]

Ryan Companies is no longer the sole developer of the targeted redevelopment site called the banana, because of the unfortunate realities of the economic recession. Now a series of new developers have been invited to continue the redevelopment of the Glenwood corridor as long as they keep a good faith commitment to the Bassett Creek Area Master Plan. Amid that transition a number of tensions arose between Harrison residents who identified the need for more affordable housing and residents of the neighboring community expressing desires for high-end shops and more green space. Like many local boards and commissions, turnover of membership and the introduction of new power brokers continues to reshape what the agenda will become therefore determining who will reap the benefits and who will not. How will the Bassett Creek Redevelopment Oversight Committee assess whether or not those community residents surveyed over a decade ago will actually reap the benefits? Or that their expressed needs will be met instead of the needs of an influx of new affluent white residents? Long term residents in Willard-Hay and Harrison continually express fear and anxiety over the ways that the processes of urban redevelopment nominally engage with them to only continue to place them in a position to have to defend their right to the community.

Inclusive Economic Growth

“[New white residents] Move here if you want to be part of the neighborhood, but don't move here if you want to make this neighborhood into where you came from. If you just want to change the neighborhood. Hopefully, you moved here for the people, not just for the housing stock. Move here to be part of the neighborhood.”[20]

The story of gentrification that emerges from our interviews in North Minneapolis highlights questions about access, ownership, race, and economic and political power. Respondents expressed fears that newer residents were in a place to dictate and often spur rapid residential and commercial change, creating feelings of isolation, disposability, and doubt in the hearts and minds of those low income and long-term residents who have endured decades of municipal neglect and public and private disinvestment.

[1] Betancur, J. J. (2002). The politics of gentrification: the case of West Town in Chicago. Urban Affairs Review, 37(6), 780-814.

[2] Willard Hay #2: White, male, long-term (10+ years) resident

[3] Willard Hay #9: Black, male, homeowner

[4] Of the 14 residents, 10 represented Willard-Hay with 4 from Harrison – 8 identified as Black, 5 as White and 1 as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; 9 males and 6 females; 4 homeowners, 2 renters, 4 long-term residents (10+ years) and 5 business owners.

[5] Willard Hay #6: Black, male, renter

[6] Willard Hay #4 : Black, female, homeowner

[7] Willard Hay #6: Black, male, renter

[8] Public meetings were held on September 14, 2015 and March 7, 2016. Per personal communications with Homewood residents, the March 7, 2016 culminated in the nomination of Homewood as a historically designated area.

[9] City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development (2017). Homewood historic district designation study and staff report. Retrieved from: http://www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us/hpc/homewood

[10] City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development (2017). Homewood historic district designation study and staff report. Retrieved from: http://www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us/hpc/homewood

[11] K. Christianson, Personal Communication, July 25, 2017

[12] Willard Hay #12: White, male, long-term (10+ years) resident

[13] Willard Hay #2: White, male, long-term (10+ years) resident

[14] Harrison #14: White, male, business owner

[15] http://www.citypages.com/restaurants/henry-and-son-is-your-new-favorite-wine-shop-7957241

[16] ROC board member

[17] Harrison #10, Black, male, business owner

[18] Harrison #10: Black, male, business owner

[19] ROC board member

[20] Willard Hay #2: White, male, long-term (10+ years) resident