The Frogtown/Thomas-Dale cluster has historically been one of the most racially and ethnically diverse communities in the Twin Cities, with a high majority of residents experiencing low incomes and high rates of poverty. Yet within this community there is a wealth of culture and affordable amenities that are cherished by the residents. Recently, the literal signs of upcoming development opportunities and the new light rail have brought the promise of investment with the threat of being priced out. Residential stakeholders are reporting unaffordable rents and significant property tax increases, while others are utilizing strategies to double-up families in homes just to be able to continue to stay in the community. These pressures have aligned with new affordable housing that has redefined affordable for historic residents and created a sense of precarity for local businesses with the presence of new businesses. The following interview analysis provides a snapshot of the narratives shared by 11 residential and business stakeholders in the Frogtown/Thomas-Dale neighborhood in our study on gentrification.

Visit the Minnesota Compass profile for this area

Affordable for Whom? Frogtown/Thomas-Dale and Gentrification Pressures

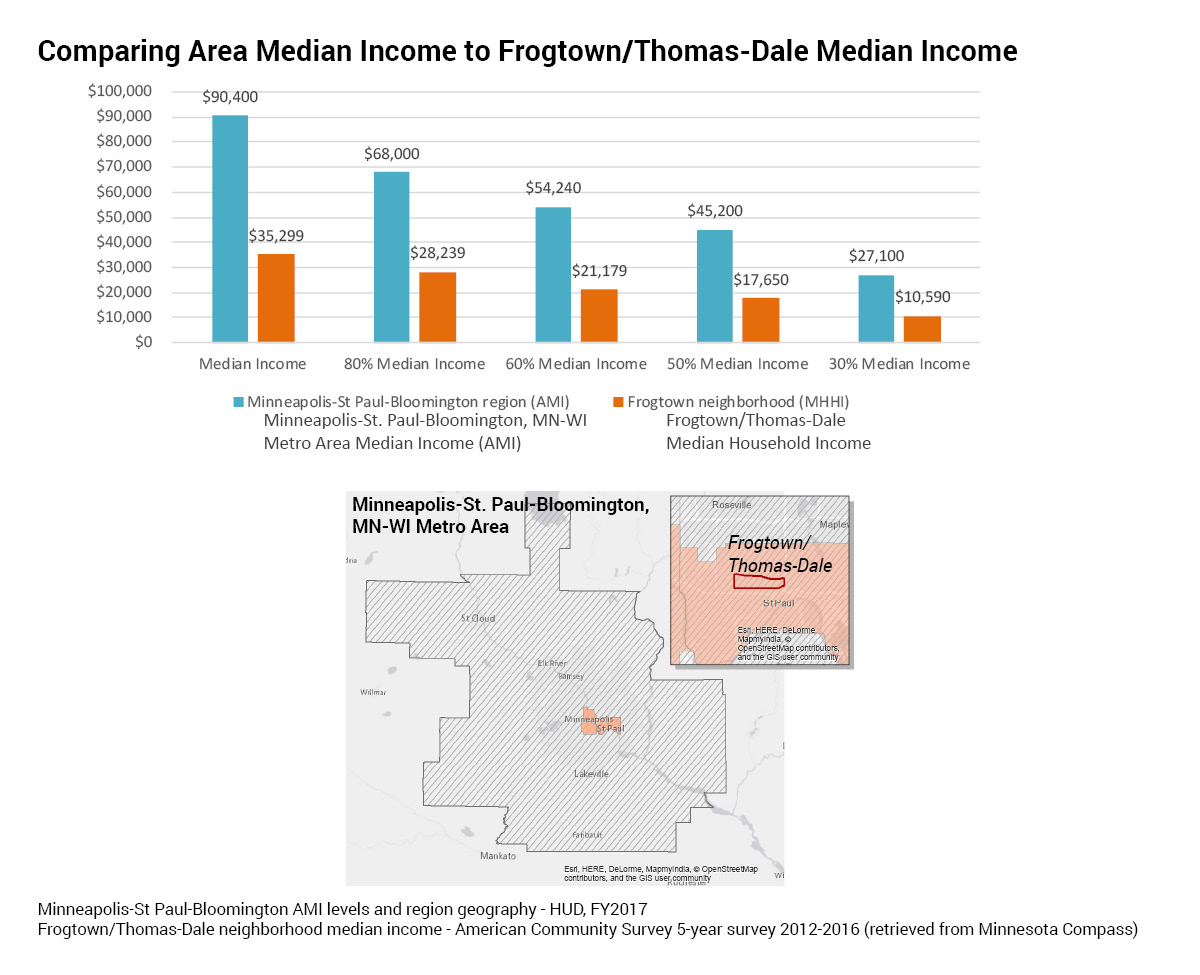

"That dramatic mismatch between the region's median income and what families earn at a neighborhood level is particularly pronounced in places like Frogtown. In stark comparison to the $90,400 area median income for the region, median renter income in much of Frogtown is below $25,000. According to data from the 2016 American Community Survey, a family in the heart of Frogtown would need to earn $34,000 to afford the median rent of $850. But median renter income in that segment of the neighborhood was far less ($22,000), forcing families to pay $12,000 more per year on housing than they can afford. The result? People who are working full time — or more — have to make daily sacrifices on basic needs, like food and medical care.

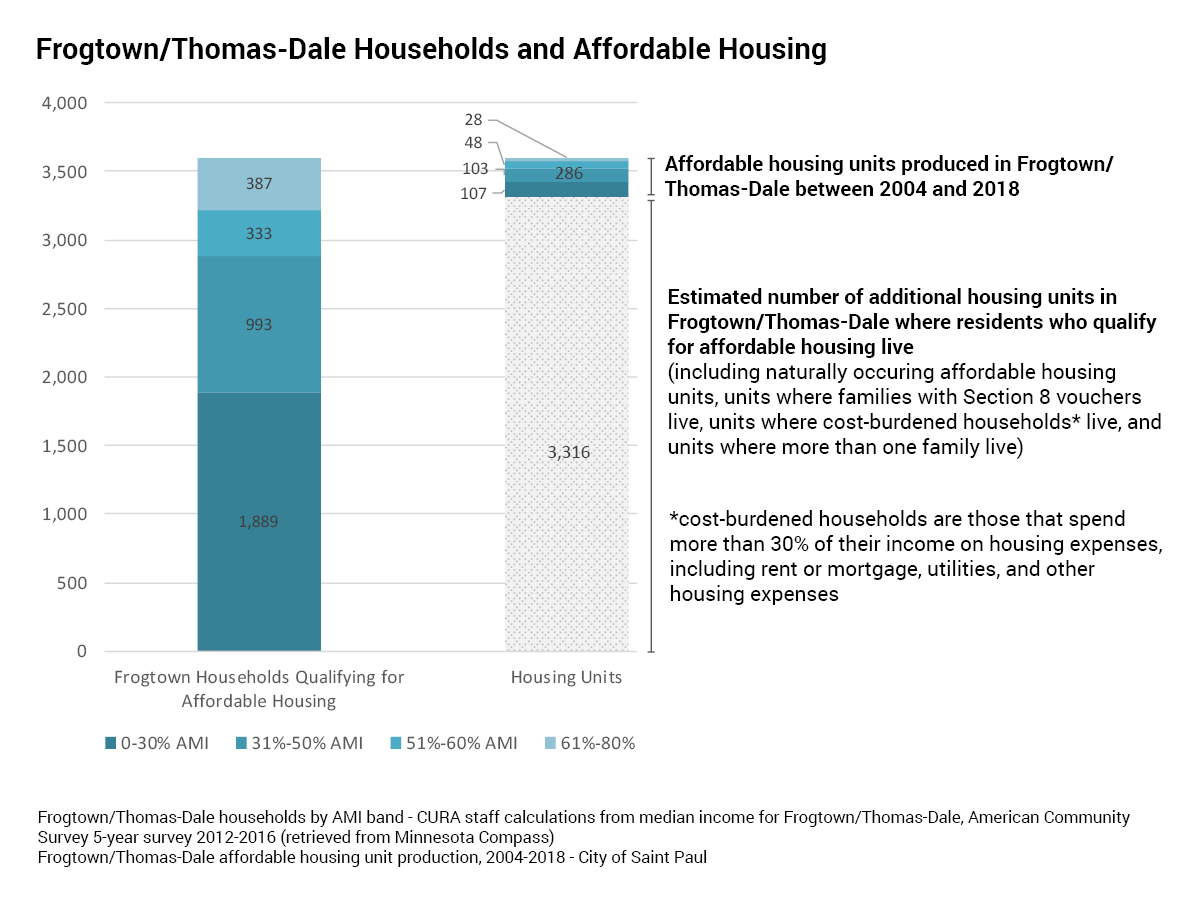

"While many families in Frogtown already have to cut back at the grocery store to make the rent, the conversation around and production of new affordable housing often hasn't adequately addressed this aspect of our growing crisis. The Metropolitan Council reports that from 2014 to 2016, only 366 of the more than 6,300 new affordable housing units produced were affordable to families earning 30% AMI or less. These families aren't just in Frogtown; across the Twin Cities region, nearly 125,000 households earn less 30% AMI.

"Already stretched beyond their means for low-market rental, families in places like Frogtown also are faced with homelessness or displacement from their community if new development or up-scaling of older properties increases their rents by even a few dollars per month. According to MHP's 2016 "Sold Out" report, more than 180 apartment properties (representing nearly 6,400 units) were sold in Saint Paul from 2010 to 2015, with a significant cluster of sales in the Hamline-Midway, Frogtown and Summit-University neighborhoods. New research to be released this month shows that, as logic would dictate, rents increase faster in properties that have been purchased than in those that have not been sold."[1]

For a metropolitan area that touts the importance of equitable development and growth, residents of the Frogtown neighborhood in St. Paul, MN are faced with the paradox of wondering whether or not new affordable housing developments are being created with them in mind or for a new class of affluent occupants. The Alliance for Metropolitan Stability and the Harrison Neighborhood Association has led a coalition of community leaders in creating the Equitable Development Principles & Scorecard as a tool for communities and planners. The tool aims to assist community, government, and developers, particularly when public subsidies are provided, to move beyond the good intentions of equitable development language toward the utilization of actual process tools that ensure that the needs and goals of existing residents are heard, understood, and incorporated into the final development project for the benefit of everyone. Equitable housing is one of five principles of equitable development laid out in this toolkit. “Equitable housing practices require evidence that families at all income levels have access to housing that costs no more than 30% of the household income.”[2] The toolkit goes further to argue that the Area Medium Income (AMI) utilized by the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to assess the income eligibility of residents for affordable housing disproportionately denies access to those living in low wealth areas like Frogtown. In short, the disparity between the incomes in the suburbs versus incomes in the city that are utilized to develop the regional AMI, has severely inflated the affordability index making it nearly impossible for anyone living in low wealth areas to “afford” the new publicly subsidized affordable housing units based on this regional metric. “There is no reason that cities and counties cannot use their own formula for affordability instead of using the Twin Cities 13 county regional AMI. It is our [Alliance for Metropolitan Stability] position that local cities and counties should use a method for assessing affordability that takes income disparities in their region into account.”[3]

From the Bronx in New York City to Frogtown in St. Paul, MN, affordable housing advocates, tenants, and their allies continue to argue that the touting of a new affordable housing development is no longer met with open arms. They know all too well that those residents living in the area cannot afford those units even at the lowest rate of 30% AMI, because the addition of wealthier communities into the calculation for median income skews the numbers making “affordable” units unattainable for those residents most in need.[4] These residents do not see these new affordable housing developments as a benefit to them, but as a tactic used to actually increase the neighborhood median income and price them out.

When the 11 community stakeholders[5] interviewed in the Frogtown/Thomas-Dale neighborhoods in Saint Paul reflected on the neighborhood changes they have experienced, they often described the ways that increasing housing costs and area demographics have come to impact both affordability for renters and homeowners alike as well as change the face of its residents and its business patrons. In this brief analysis of our interviews, we will pay close attention to the ways that new affordable housing developments and rising rental costs are pushing out low income residents and reducing access to naturally affordable housing options, while also examining what it looks like when new businesses begin to enter a racially diverse community like Frogtown while others leave.

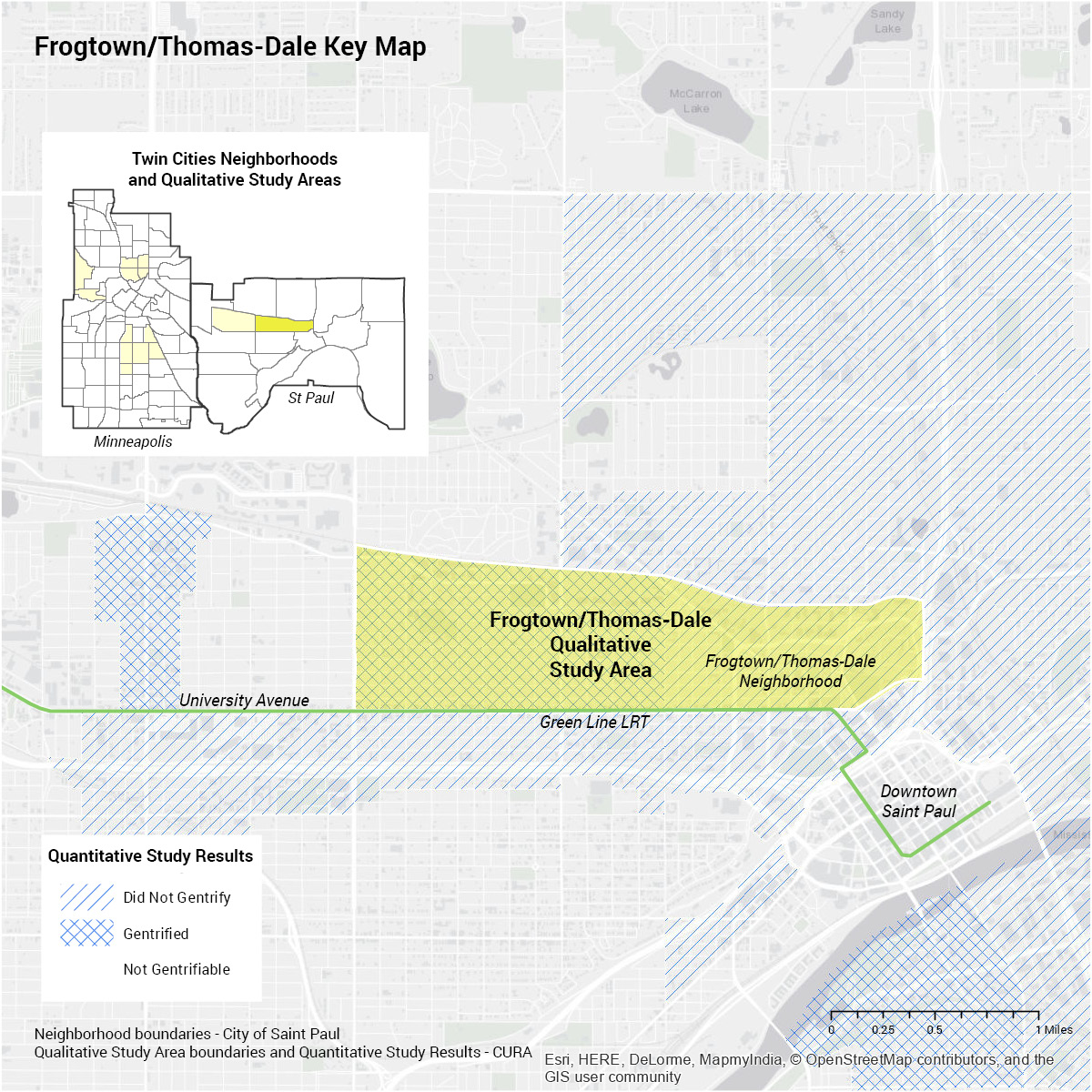

The Frogtown/Thomas-Dale neighborhood is a community adjacent to downtown Saint Paul with Rice Street as its most eastern border and Lexington Parkway as its most western border, where it meets the Hamline-Midway neighborhood. Sharing the University Avenue corridor with the Hamline-Midway neighborhood to the west, the Frogtown/Thomas-Dale neighborhood has been similarly impacted by targeted transit-oriented development. Since this neighborhood is further east along the Green Line light rail and development has been slow in reaching this corridor, this community has not yet seen the full impact of new business development that those living further west along University Avenue (in Hamline-Midway) have reported.[6] The Frogtown/Thomas-Dale neighborhood is one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city, with the most racial diversity and the majority (over 60%) of its households occupied by renters. In addition, this area of Saint Paul has experienced the largest decline in population in the city between 2000-2010 as a result of the foreclosure crisis. The Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) has gone further to assess that across St. Paul, the after-inflation median rent rose 3.5 percent from 2000 to 2014, while in Frogtown, it rose 31 percent ($414 per month, after adjusting for inflation) during the same period. [7]

The Rent is Too D$^M High!

The community stakeholders in Frogtown, particularly those who are a part of the rental population, were astutely aware of the fact that the further west (toward the Hamline-Midway neighborhood) you lived, the more expensive and unattainable it became. In a community that has historically been affordable and accessible to low income ethnic and racial minorities, many have reported that they have been forced to move further east to the eastside of Saint Paul and into outlying suburban communities to find a place that they can afford to live, an observation that was also reiterated by many of our community stakeholders in Hamline-Midway.

“…I work in Frogtown, and I wanted to stay close to my mom and my family. All of my family lives in Frogtown [originally from the Rondo community]. When I had to move back to Frogtown, after moving to the Eastside, it was an emergency. And I had to hurry up and get out of this space I was in … I found something in Rosemount [suburban community] for $759. It was affordable… I was not able to live in Rosemont [lack of reliable transportation]. Thank God, I work with organizers who knew of another organizer who owned a property [in Frogtown]. And I moved into that space even before he had even turned it over yet. I helped him clean it. I had to hurry up and get out. Once I got there, my rent does not reflect the property [subpar conditions]. The landlord's a good guy, but it does not reflect the property.”[8]

In addition to a lack of affordable housing options in what many have reported are subpar living conditions in the existing housing stock in the Frogtown/Thomas-Dale neighborhoods, other community stakeholders reported that it is not only the inflated cost of existing housing stock that is out of reach for the current rental population in the area. The affordable housing units that are being developed along University Avenue are simply out of reach for the low income residents who currently live in the area.

“I mean, on one hand there's a lot more development, and it's of a type-- it's tax credits, affordable housing, retail on the bottom, two or three stories of what's termed affordable housing, up. The oddity of that is that-- with the affordable housing is [laughter] the qualifiers are often for people who make more money than people who actually live here.”[9]

New affordable housing apartments built with state and federal housing tax credits are based on the Area Median Income (AMI) of the region, which according to HUD was set at $90,400 in 2017.[10] Yet the local AMI for Frogtown/Thomas-Dale according to American Community Survey (ACS) is $35,126.[11] Additionally, affordable housing units often come with the requirement of higher credits scores, caps on the number of tenants per bedroom, and stringent background checks for all potential tenants, all of which makes the new affordable housing developments not only unaffordable for historic residents, but also inaccessible.

Frogtown/Thomas-Dale stakeholders have also reported that landlords are no longer accepting Section 8 vouchers and the options for true affordability is dwindling. For many, this means the ability to live where you work will never be an option, as naturally affordable housing options become fewer and farther between.

“I'm just seeing a lot of-- and a lot of condo buildings coming up on University that can’t nobody afford to live in. My son actually wanted to stay in Frogtown, but because he wasn't able to find anything affordable for him and his girlfriend, they ended up moving to Minneapolis. But he works over here.”[12]

...

“Then people started buying up the homes for rental properties and putting people in there, and not even keeping up the homes. And charging ridiculous amounts because of the fact that they're so close to the light rail and stuff like that, but at the same time they're not having any type of livable conditions in their home.”[13]

…

“I kind of feel like I'm in a cycle of, I have to pay this $1000, which I cannot afford. The house, like I said, bless his heart. He's a good landlord but he needs to do a lot of work on that house. There's something wrong with the plumbing… I turned the heat on - I think it was in November or December when it started getting cold - to 68. My bill went from $98 to $341. And so I turned my heat down as far as it could go and I bought some jogging suits [laughter].”[14]

…

“It's not affordable. It's not affordable. It's not affordable at all. And now people-- I know now because I actually did a housing survey and stuff. So I know now, a lot of landlords are not even taking Section 8 anymore. So that's stopping them. And the affordability of Frogtown is getting up because I know my friend, now, his Section 8 vouchers are for like maybe $1200, and that's a two bedroom that he's in. And he has a daughter and a son. So that's pretty up there, especially when it's not even kept up.”[15]

Our community stakeholders continued to share stories from their own lives, or from their close family and friends that indicate that many are struggling to maintain housing in the Frogtown area. As they acknowledge their experiences with rising rents amid the persistence of subpar living conditions, the inaccessibility of the new affordable housing complexes, and a dearth of landlords willing to accept Section 8 vouchers, they also described how many people are finding ways to maintain residency in a place they cannot afford by doubling up. Sixty percent of Frogtown’s renting households are cost burdened (compared to 50.8% in St. Paul as a whole) and are simply trying to hold their housing in a market where naturally affordable housing options are dwindling.[16] As a result, our community stakeholders are reporting that they are forced to develop alternative survival tactics to retain residency in the area.

Doubling Up: Strategies for Surviving During the Housing Affordability Crisis

The primary goal for most of our community stakeholders is to retain residency in Frogtown, maintaining close proximity to public transportation as a means of mobility, and stay close to the social and economic networks of support that help them raise their children and their ethnic or racial communities. To do this, many are forced to take on additional roommates and in many cases, without the knowledge of their landlords.

“I would be very curious to know what the houses are being rented out for. Because I never see a single family living in any of them. This white house, I've seen a group of five college students, or right now I think there are like two or three single women with their kids. So it's always cost sharing, in the houses, because there are multiple bedrooms, so it's obviously rental situations where people are sharing the cost.”[17]

Similar to the tenement style living that many were forced to live in during the first half the 19th century in places like New York City and Chicago, based on what some reported in our interviews, single family dwellings are being divided up into multiple living spaces to accommodate a growing population of need. In this case, it appears there is a growing population of residents living in the Frogtown/Thomas-Dale area who can no longer afford to maintain residency by themselves.

“Double up means that it is that-- so my cousin lives with my other cousin…and you're only supposed to have only one person or one family living there. He has to live there.”[18]

During the first half of the 19th century, tenement housing became associated with overcrowded dwellings with little ventilation, sparse lighting, and a lack of adequate plumbing. This led to legislation that banned the building of all tenement housing, particularly in New York City, and established plumbing, lighting, and architectural standards based on the number of families living in any dwelling of a particular square footage. Based on what our community stakeholders have shared with us, there are many families and/or friends illegally housed in homes or apartments in the Frogtown/Thomas-Dale area. This is undoubtedly placing pressure on an already subpar housing stock, but it is out of necessity that those low-income residents resort to such arrangements.

“A lot of that happened in the foreclosure crisis, so we really bought at the height of the market and we were able to ride it out. But we saw a lot of our neighbors lose their houses. So you see across the street, that house has been vacant for seven years. So that was Susan and Esther[19], and when we were here Susan and Esther were there. The Smiths were next door. There was a long-time renter to the right, and so we had a number of years when we were here when we really knew each other. And since then a lot of those have turned over. The families that owned and lived there have turned into people who own the houses don't live there, but they rent them out.”[20]

Increased Property Taxes: Homeowners Feeling the Early Pressures

Our community stakeholders, some of whom are homeowners, have expressed a very different and yet related concern about their housing costs. Some homeowners (mentioned above) have been forced to open up their homes and take on renters or simply fear the day they are so underwater in their mortgage, their homes are foreclosed on simply because of rising property taxes and the inability to keep up.

“And you know, one of the things we always knew is that with light rail coming in, that around the station areas in particular, that the property values would start to rise. Now we're starting to see that. Years ago when I was involved in the station area planning even before light rail came, years before light rail came in, there was a real estate guru that predicted just kind of what we're seeing. And he said that the development-- there'd be a lot of development. High intensity. Developments closer to the University [of Minnesota]. And it would just slowly begin to creep down here. And unfortunately our neighborhood would be one of the last ones to see it. And so it's given folks even more time to invest in these properties and to hold onto them. So we're starting to see the increase in these costs now.”[21]

…

“Property taxes have been crazy. My taxes have gone up every year, and fortunately, my salary has gone up every year.”[22]

…

“One is our taxes are going up. We're so fortunate and blessed that we were able to pay off our mortgage. And for folks who are on a fixed income, I can see how those taxes and fees that we get from the city, compounded with insurance, can be a hardship for folks. Especially for folks who are older than me.”[23]

…

“But what happens when transit comes in is that, you know, property values go up. And so people that could afford to rent at one time are now unable to afford the property taxes and rent goes up. We saw our value increase pretty quickly in the three months that we lived there. As soon as the light rail opened, when we got our sort of statement of our value, I think we increased by like 5,000 in three months. Which we were both shocked, but not shocked.”[24]

Reports of drastic increases in property taxes were coupled with our stakeholders noting that they were fortunate enough to either have had salary increases at their jobs or be long term residents with paid off mortgages who call themselves “lucky.” These community stakeholders acknowledge their own privilege in being able to maintain and grow with the rising costs of the area compared to their neighbors who they know are not in the same positions. As targeted development has come to the University Avenue corridor, investors have bought up undervalued properties and increased the rents, and homeownership costs have increased at staggering rates, it has become much more challenging for many to see the ways that business development has followed suit because it has shifted at a much slower pace.

Business Development in Frogtown

“I think just because I work at the Met [Metropolitan] Council, I know the Met Council likes to talk about a lot of the development and stuff that's happening along the light rail, and how much investment has happened. But there's not a lot of talk about the businesses that suffered, and the debt that they're in, even though if they survived, they survived because they've gotten loans often from the Met Council or the city. But they're a loan. They weren’t grants, so they're more in debt. And so if people are not visiting those businesses, or they're just still holding on, or the ones that did fold, there's not-- it's not clear the net is, I should say.”[25]

National images of gentrified neighborhoods often reflect a Starbucks Coffee, trendy café, tech center, or Whole Foods in place of what was once a historic low-income community with dilapidated buildings that housed local mom and pop restaurants or underserved community service centers. Along University Avenue in Frogtown, there is a different story to tell. As the aforementioned community stakeholder noted, some businesses were able to survive through the construction of the light rail and they have become the pillars of success for the city. While those that had to close their doors in the process are only known to the local residents that used to frequent their establishments or are business owners who strategically moved out before the impending disruption.

“I was on University Avenue at that time [prior to the light rail], and I was only allowing my customers parking right on the street. Most of University Avenue properties do not offer off-street parking, because properties are built so close to each other. And most of my customers are parking-- so my grocery store, the front of my grocery store, would be for cars and able to park for cars. After the light rail comes, none of those customers are able to park on University Avenue, therefore myself I have to get out. Otherwise, if I don't get out soon enough, I will be bankrupt, myself.”[26]

For the businesses that have survived, yet have faced further debt as a result, the impending new clientele may be the hope that will spur development to actually come. Ironically, the rise of a new affluent population will be the saving grace for some businesses, especially if they can attend to these new patron’s tastes, while the advent of these new patrons might very well be the thing that others fear will make maintaining residency in Frogtown impossible.

…

“So I see the rush of development coming in again in the four years. There is some strong community driven development. Like the BROWNstone building, which I think went through a community process. But then there's all these other buildings that are just coming in to make dollars off of the proximity to the light rail. Now, in actual Frogtown, we haven't seen the huge developments coming yet, but now every time I go home I see new signs saying, "Coming soon. Coming Soon. Coming soon" down University, and so we know it's coming soon [laughter]. But when you get to west of Lexington it's already happened.”[27]

While some Frogtown residents hold their breath as the more frequent “Coming Soon” signs appear, they acknowledge the great work that many local community members have played in ensuring that there are some community driven developments. Yet the anticipation of the inevitable seems to be so clear for so many as they just wait to see what new developments will soon happen around them. Although no chain restaurants or big box stores have opened their doors in the Frogtown neighborhood as of yet, the rise of the new trendy café has made its debut.

“So I think we're [a new business on University] kind of bringing a different crowd of people to the area, like newer… people who aren't familiar or wouldn't normally stop in Frogtown. I guess to kind of like visit the area, to see that it's not terrible, so… But there's a lot of people who would come in and they're just like… have this certain idea of what a bakery should be. And then when they don't see that, they're just like, well, this isn't kind of a bakery that they're looking for. They're looking for a more traditional-- more like a bread shop kind of bakery… I would say more local people. They're kind of looking for more of like the… I'd say, more affordable items or stuff like that…. Like bread shops or they're always looking-- I get a lot of doughnut requests [laughter].”[28]

This business owner, who grew up in Frogtown, desires to bring something different to the area and as a result they have advertised their pastries as pieces of “edible art.” A business that prides itself on not being your typical bakery is filled with “global fusion food” perfect for the patron jumping on and off the light rail.[29] After the building where this business now resides sat vacant for about 3 or 4 years, these owners fused their love for food together and created a high-end bakery with no donuts or loaves of bread.

From a business standpoint, this new trendy bakery will undoubtedly draw attention to the aesthetic tastes of a new class of affluent residents looking for high end pastries with a global twist at a high price per piece. The once drab boarded up building is now a modern and sleek silver and dark blue storefront. Inside it boasts stainless steel appliances, countertops and chic décor with a display case featuring its globally fused pastries individually wrapped. This new business has definitely found a niche as they have thus far been able to successfully lure in those who, as they stated themselves, would not typically come to Frogtown.

As the Frogtown/Thomas-Dale neighborhood continues to change and residents fight to maintain residency in an increasingly expensive housing market, frequent local businesses, and retain their connections to their distinct cultural and ethnic communities, it is clear that this will become even harder for those who are not fortunate enough to receive regular raises, have paid off their homes, or enter the community as a young professional. For a majority of the residents (over 60%) who are renters, the future is looking increasingly bleak as median rent increases with more affluent residents moving in, rehabbing, and investing in an area where a majority of its residents live in impoverished conditions. For Frogtown, a once affordable community for individuals with low incomes and residents of color, the new development begs the question, who is the neighborhood affordable for now?

[1] Carolyn Szczepanski, Director of Communications & Research at Minnesota Housing Partnership

[2] http://thealliancetc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/EquitableDevelopmentScorecard.pdf

[3] http://thealliancetc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/EquitableDevelopmentScorecard.pdf

[4] https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/what-is-area-median-income-affordable-housing-cheat-sheet

[5] Of the 11 residents and business stakeholders, 6 identified as Black, 2 White, 2 Asian and 1 Latina; 5 males and 6 females; 4 homeowners, 2 renters, 3 long-term resident (10+ years) and 2 business owners.

[6] Link to the Hamline-Midway blog page

[7] http://www.startribune.com/counterpoint-criticism-of-study-on-gentrification-missed-key-points/405329726/

[8] FTD #11: Black, female, renter

[9] FTD #2: White, male, long-term resident (10+ years)

[10] Minneapolis-St Paul-Bloomington AMI levels and region geography - HUD, FY2017

[11] Frogtown/Thomas-Dale households by AMI band - CURA staff calculations from median income for Frogtown/Thomas-Dale, American Community Survey 5-year survey 2012-2016 (retrieved from Minnesota Compass)

[12] FTD #7: Black, female, long-term resident (10+ years)

[13] FTD #5: Black, female, homeowner

[14] FTD #11: Black, female, renter

[15] FTD #5: Black, female, homeowner

[16] American Community Survey 2016 5-year estimates via Minnesota Compass Profiles, http://www.mncompass.org/

[17] FTD #10: White, female, homeowner

[18] FTD #11: Black, female, renter

[19] Pseudonyms used

[20] FTD #10: White, female, homeowner

[21] FTD #3: Black, male, long-term resident (10+ years)

[22] FTD #1: Latina, female, homeowner

[23] FTD #3: Black, male, long-term resident (10+ years)

[24] FTD #6: Black, male, homeowner

[25] FTD #1: Latina, female, homeowner

[26] FTD #9: Asian, male, business owner

[27] FTD #6: Black, male, homeowner

[28] FTD #8: Asian, male, business owner

[29] http://www.citypages.com/restaurants/silhouette-university-avenues-new-global-fusion-bakery-and-bistro-8425651